Shazia Javed’s 3 Seconds Divorce (now streaming on Netflix) is a new documentary that sheds light on a practice that allows men to divorce their wives simply by saying the word divorce three times. Commonly called triple-talaq, or triple-divorce, this instant, oral divorce can only be granted to men. In India, Muslim women have been fighting to have this practice legally abolished. The film takes you into this world through Lubna (who finds herself in this position), eventually joining a movement that leads to a ban on instant, oral divorce in India.

We asked Shazia about the documentary this week.

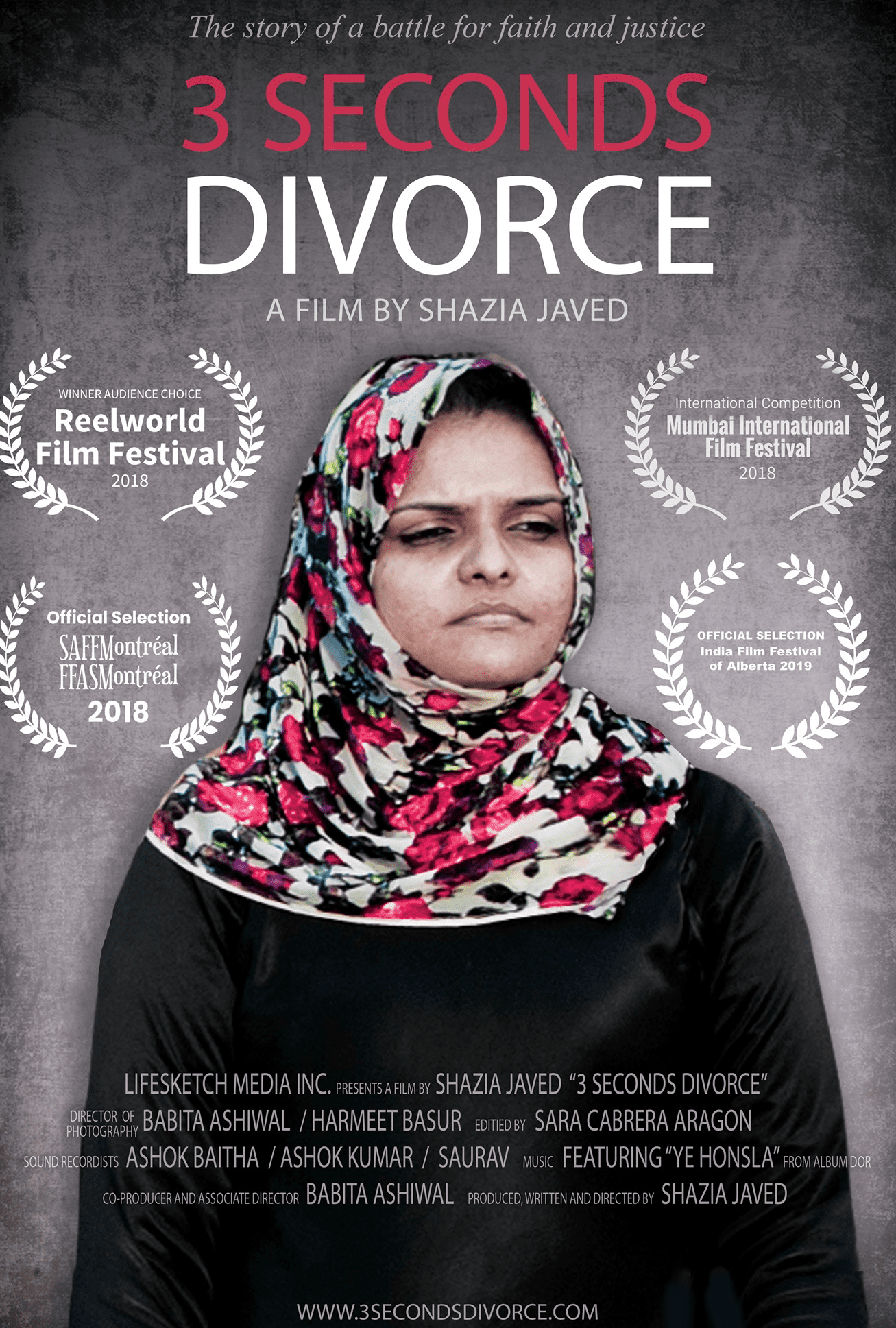

Director Shazia Javed

SDTC: When did you first learn of the practice of oral divorce? How has your view of it changed over time?

SJ: I grew up in India and first heard of this practice as a child. Someone really close in my extended family had experienced it. As I got older, I had many questions: Why are the women in the weaker situation (i.e., the receiving end)? How can something like this be legally acceptable? Is this really a part of Islam? Why are only certain kinds of people getting to make decisions? So I immersed myself in reading a lot about this for a while. I wrote a letter to the editor of a national newspaper when I was only in high school. Even then, I wrote that this needs to be done away with. Unfortunately, many years later it is still prevalent and now that I found a powerful tool in filmmaking, I knew I had to delve deeper into this issue.

My view was, and remains, that this is legal discrimination. While making this film, I have come to better understand the complexities around this issue, the socio-political context in which it exists at least in India, that this is a product and tool of patriarchy, that women have been deliberately kept out of authoritative spaces occupied by misogynist religious leaders. I now also understand the full extent to which it impacts women. I have built all these insights into the film.

Can you explain what halala is and what that entails? How does this fit into the oral divorce law?

Halala is the process of making a woman permissible to the man after he has divorced her. So if a man says the word talaq three times in one go, then the divorce is considered irrevocable and the couple cannot live together unless the woman goes through halala. That is, she will have to marry someone else and that marriage will have to be “consummated,” and that man will then give her a similar divorce. Only after this process can she go back to her original husband. Most of these are arranged as one-night marriages by relatives, and women often go through these because they might have young children and no where else to go. So halala is intrinsically tied to oral divorce because first you accept a hastily given, poorly thought-out divorce with no prior planning of who will get what and live where and then to make the matters worse it is treated as something that cannot be revoked unless you put the woman through all of this. This is how much weight is given to words spoken by men. Their words are non-retractable and as a result, women are put through such abusive situations. Halala is justified on the basis of skewed notions of honour; it is in essence “a punishment to the man for giving instant, oral divorce because he has to bear the fact that someone else had sex with his wife.” The woman’s experience is totally ignored in this discourse created by patriarchal faith leaders.

What are the major concerns that come with oral divorce? What were you hearing from the women who experienced it?

Well, a man may have said those words in the moment and the couple may want to live together, but the entire process of halala makes it difficult, demeaning and thus sometimes impossible. The sudden nature of this kind of divorce many times leaves the woman prone to homelessness, as she may have nowhere to go. There is no clarity on who will keep the child, as no time has been given to any kind of arbitration.

What I also heard some women say is that this kind of divorce is used as a threat to make women do things they are uncomfortable with or that they dare not argue with their husbands out of fear that the husband might get angry and say the words. This kind of divorce sets a power equation in the marriage from the beginning. And with today’s technology, some faith leaders have been accepting divorce sent through WhatsApp messages, speed posts or email. There are times that the woman isn’t even aware that the man has already said the words and divorced her in her absence! The women are increasingly and rightfully angry. They are refusing to accept this is the word of God. They are pushing for change in the laws. This is what led to the movement for a ban on this kind of divorce in India.

While making this film, what did you uncover that surprised you?

I was surprised at how common the threat of this kind of divorce was and how so many women felt it. I was shocked that halala still exists. I was also surprised that many people who do not necessarily endorse this practice are still silent on the issue and are willing to push it under the rug because they don’t want to disrupt the status quo or ruffle feathers.

Women’s experiences are invalidated, considered minor, dispensable and their voice a threat to “larger interests.” In the film we see how some women’s efforts finally lead to many more men and women becoming vocal on the issue. We followed the women of Bharatiya Muslim Mahila Andolan, the Muslim women’s activist group, for about three years, and we see them build the momentum.

Have you spoken to any of the subjects of your film recently?

I am in touch with Dr. Niaz, who is the co-founder of Bharatiya Muslim Mahila Andolan (BMMA), the activist group we follow in the film. They are continuing the work and want a uniform procedure stipulated for Muslim divorces in India that includes time for arbitration and reconciliation. They are also advocating against polygamy and recently won a case regarding Muslim women’s right of entry into a place of worship they were barred from.

Indian Parliament is currently debating whether to make triple-divorce punishable by law and BMMA is actively formulating suggestions on that. However, this proposal for criminalization has further divided the opinion. Not everyone thinks it is a good idea and there is a fear that such a law might be used against Muslim men at large. The thing is, Muslim family law in India is open to too many interpretations and there is still a lot of change that needs to happen for legal discrimination faced by Muslim women to end.

What do you hope audiences take away from this film?

The most obvious is that instant, oral divorce has a lot of negative impact on women and families. I hope people take away that this practice isn’t unchangeable, that this can be and should be done away with. And I hope that this happens internationally, wherever this practice exists, to whatever extent, and I have heard from Muslim women in Canada, the UK, and Pakistan who have been divorced this way.

This is why I am glad that the film is now streaming on Netflix and is accessible to audiences worldwide. The other broader theme of the film is women’s activism, especially those who are doubly marginalized. With this film, I have striven to show the cost of such activism, how hard it is and how much personal sacrifice goes into the making of a movement. Each small change comes at a great cost.

I hope people will watch this film and will have respect for the change that came about and continue the struggle further. I also hope people will support grassroots-level women’s rights organizations, especially the ones that are under-resourced and doing great work in volatile political environments. With this film, I want to change the notion that Muslim women and women of colour lack agency. They are fighting their battles and what they need are strong allies.

3 Seconds Divorce is now streaming on Netflix.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram