It was Asexuality Awareness Week in October and without typing those words into my search bar, the only added asexual awareness that I noticed was my own squirming tangle of anxiety about the topic.

Should I talk about it? Should I be the one to speak up? Would people get it? How many people will have never even heard of asexuality? How many of those same people will be just SO confused about why I think I should share this sort of thing?

So I stayed quiet during Ace Week.

Judging by the lack of discussion about this topic, it seemed a lot of other Aces were having similar thoughts. It can feel hard to ’’come out’’ when there isn’t a clear place of visibility on the other side of the closet door. That doesn’t mean there’s no Asexual closet; for many Aces, the coming out timeline is measured by how long we can last until the pain of the silence breaks us.

I have personally always kept my head down about my own asexuality, although I’ve identified with the term since I was 15. When I first came across the definition of asexuality, I not only instantly identified with it, but I fit the definition so thoroughly that I had absolutely no concept of what it would be like not to fit the definition. I realized I had no idea how the rest of the world experienced sexuality.

I still have no idea what sexual attraction actually feels like, even though I live in a world that seems to simultaneously revolve around it while somehow managing to make it an off-limits topic of discussion.

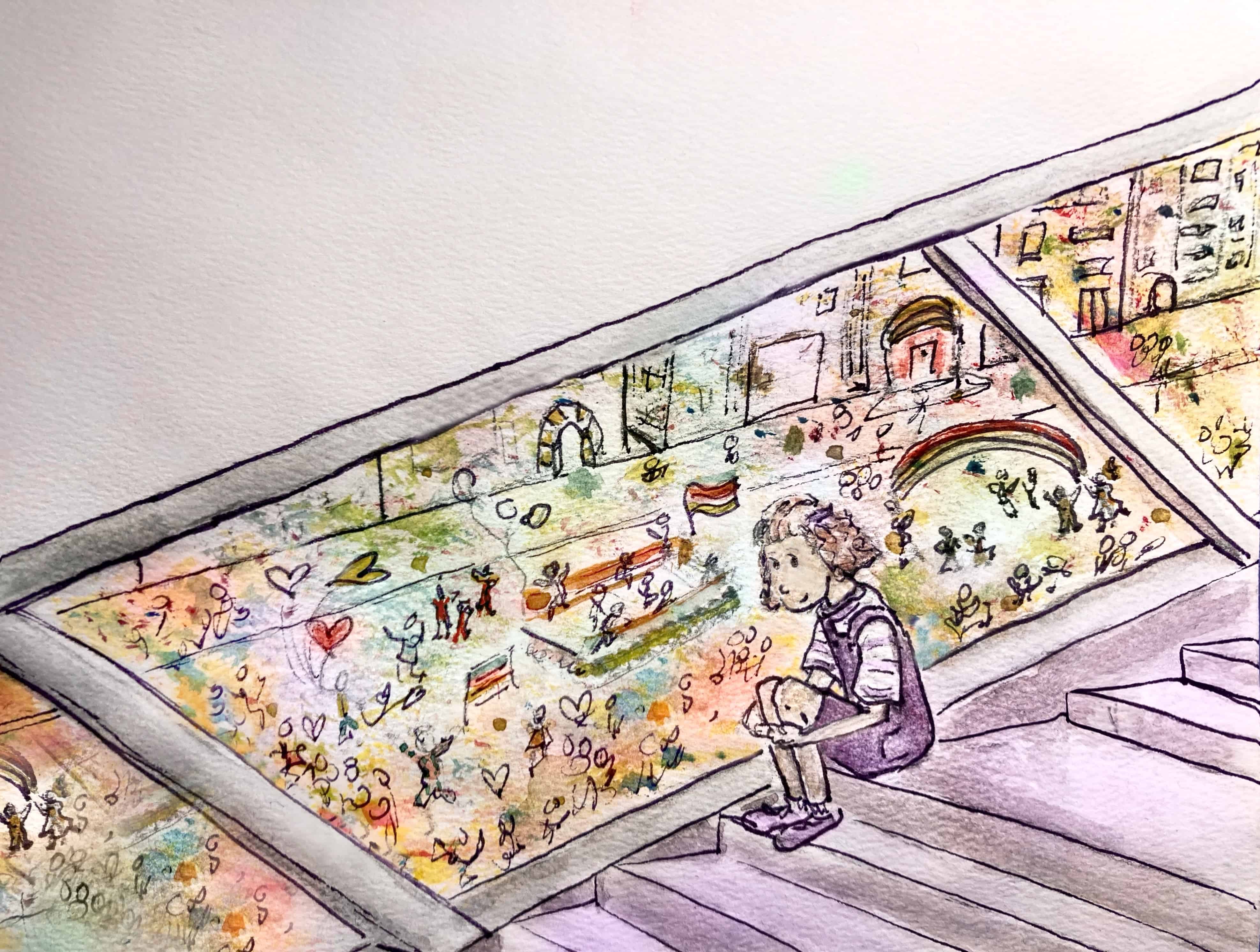

For Asexuals, the world can feel like it’s spinning at a different speed. I started to feel comparably lost at about age 10. There was something… unreachable; something about the way in which my peers existed that I could not grasp. It made me scared to grow up. I dreaded getting older. Every birthday seemed like a punishment that banished me further away into an existence apart from the rest of the world. Around the age of 12, all the other humans my age started obsessing over things that didn’t seem real to me. At first it felt annoying– I thought they were just imitating what they’d seen in teen movies.

The first time someone asked me if I had a secret crush, I thought, “I know who I want to be friends with. Some people are nicer than others, some are funnier, some are smarter, and I know who looks nicer…” But when they asked me who I thought was ‘hot’ I had no concept of what the answer could be.

I waited for what I’d thought to be fictional to get real for me. Meanwhile, every movie, every book, every song, and every human plotline revolved around a focus I didn’t know. I waited to grow into the understanding of this missing piece and become a full human.

I didn’t.

To an asexual who hasn’t learned of this identity yet, it can feel like hiding is a part of life. Pretending becomes natural and constant. It’s a life so desperately invisible that there is no language to bring it into view. I became completely sure that being the way that everyone else in the world seemed to be would never be possible for me. It hurt too much to try and fit, and I became desperate to stop trying. By the time I was 18, I’d had 3 inpatient admissions to Youth Psych Wards.

In the initial research that mapped the flow of attraction through The Kinsey Scale, there were numbers from 0 to 7 that marked heterosexual identities to homosexual identities onto this full spectrum of attaction. There was also a significant portion of interview subjects who did not experience any attraction to anyone. They were marked with an X, gathered as connected anomalies, and put to the side of the graph. Off to the side, anyone who knew the world through the same lens as ‘group X’ did, grew up feeling wrong, broken, inhuman, and unable to exist with the world on this graph of love.

At nineteen years old, while living in the middle of New York City, one day I found my home at the center of the world swarmed in a rainbow. From the window of my apartment I watched the vibrant chaos of the Pride parade from a place that seemed like a safe distance from the tidal waves of colour. It made me feel too young. Too small. Too wrong. I still had not grown into the colourful life that the rest of the world lived in. I still couldn’t understand it.

Even though I didn’t see the way I felt love represented in the Pride Parade that day in New York, I knew that I had a lot of love to give, and that my love belonged to that flag. I just needed a place to put it, to plant it, and to grow it. For asexuals, the key to opening the closet door is the grounding knowledge that we are not alone; to know that outside of the asexual closet there is a destination where one can exist wholly, feeling the freeing confidence of believing in your own capability to love.

In the 90s, the internet brought with it the potential for that knowledge. Through their fear and self-doubt, people started to find ways to share their varied human-experiences with one another. People whose experiences had previously gone unseen and unrepresented threw anonymous airplane messages into the screen world. Those messages were caught, understood, answered, and reflected back. In this reflection, those who had up until this point lived invisibly were finally able to see themselves in others’ experiences. Through the safety of anonymity, a space for authenticity was found. Group X found each other.

As Angela Chen in her new book Ace has put it: “The ace world is not an obligation. Nobody needs to identify, nobody needs to stay forever and pledge allegiance. The words are gifts. If you know which terms to search, you know how to find others who might have something to teach.”

It’s been 25 years since asexuality gained recognition, and asexuality is still battling its way into mainstream media. Looking at life through the asexual lens offers us the opportunity to expand our understanding of what the world is and of what it can be. When we work to see together alongside others who have alternative opinions and viewpoints, we forge a bridge across the distances we feel by celebrating our differences. Asexual awareness is essential and beneficial to us all.

In the past few years, I’ve been growing acceptance for who I am, and the Asexual identity helps me to do that. I spent years feeling like I’d never be complete, believing that I could never grow correctly. And now, while I feel a sense of grounding acceptance in the roots of who I am, I know that it isn’t about growing into something. I’m not waiting to be complete… I can be complete as I am. I see this work as the direction we are all moving toward in the acceptance of our rainbow of experiences. Humans experience attraction on a spectrum. We might have the same labels all our life or we might find that the way we are drawn to others changes over the course of time. With that there comes the opportunity to come out into new versions of freedom.

Ace people are not ‘lacking’ in love. Ace love is PRESENT in a beautiful and unique way. No matter who you are or how you identify, it’s the way you see love that matters. During times when the heart is strained, times when it hurts to keep going, we listen to hear the echoes of others who voice their differences over the distance that they also feel, and there forms a space to feel, together.

This is why we need to talk.

To shout out our pride.

To celebrate the full force of ALL that love can be.

There’s more to love than any one person can know. As we listen to one another and begin to broaden our knowledge of love, our hearts will collect the strength to connect with hope. When ‘group X’ finds one another and is able to express how their love presents itself, the rainbow strengthens.

Katie (@katie.nora) is a 22 year old Toronto-based theatre artist and writer. To connect further, find her on Instagram @katie.nora and online at KatieReadyWalters.com where she writes about mental wellness, communication, and art.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram