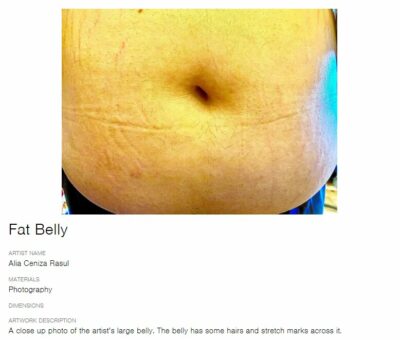

A few weeks ago, I submitted a close up photo of my fat belly to the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) as part of their #PortraitsofResilience project. It is now posted in a gallery on their website, for all to see, in all of its stretch-marked glory.

This is something that I would have never imagined myself doing. Even just a few months ago, I would have been mortified at the thought of people seeing my belly in full display, having spent my entire life invested in making my belly go away, or at the very least hiding it. So what happened? A global pandemic.

When the world went into lockdown, I was already very familiar with the body positivity movement; I consumed all content, and worshipped Lizzo. I knew that fat wasn’t a bad word. I knew that fat bodies could be beautiful, and that I had every right to exist as a fat person. I intellectually knew all of this, but I did not feel it to be true.

When I saw fat bodies being celebrated in the media, I zeroed in on the fact that the people in the photos still had somewhat flat bellies, tinier waists than mine and just the one chin. Seeing picture perfect photos of beautifully made up fat women made me feel less alone, but not necessarily more comfortable in my own skin.

I had internalized body positivity to mean that a person could be fat, but only in certain terms: if you have a beautiful face, the right clothes, a cool personality, then you are the right kind of fat, and I told myself that I was not that. So much body shaming came from my own mind, and I didn’t know it.

There is no doubt that the loss of connection with friends and family during the pandemic dealt a large blow to our collective mental health. However, being forced into isolation also meant a removal from the public gaze. It was a relief from the incessant policing of my body, an unexpected silver lining. Because I was no longer preoccupied with everyone else’s fatphobia, I had the space to deal with my own.

Thinking back on the last year, I’ve had a few “fat moments”, pivotal junctures where I felt significant shifts in my relationship with my body.

Fat Moment #1: I called myself fat for the first time in public.

Through the new normal of Zoom-hosted panels and events, I was introduced to an accessibility measure called visual description; a means to inform individuals who are blind or who have low vision about the visual content on screen relevant to the conversation. A part of this includes having each speaker describe themselves in detail. A dear friend of mine and I hosted a conference together and during our first panel, she included the word ‘fat’ in her visual description. Hearing her say it inspired me to include it in my own. I cringed as I did it and felt nauseous immediately after. Despite the nausea, I hosted 9 events that weekend and called myself fat at the top of each one.

It did not go unnoticed. A few of the conference attendees began a discussion around our visual descriptions and expressed that while they understood the intention of choosing to call ourselves fat, it was uncomfortable for them to witness it. Some wondered why we would choose to fat-shame ourselves, or why we didn’t use euphemisms such as curvy or voluptuous instead. It was fascinating, but also weird to come across a message thread of people you don’t know, talking about you. They couldn’t wrap their minds around the idea that the word fat could be anything but pejorative given its history and their own relationships with it. I understand that. I didn’t engage in the conversation, but I wish I could tell them what I know now. I felt the same extreme discomfort in the beginning, but after several months of calling myself fat, the nausea faded. One of the things I most feared was to be called fat or to be thought of as fat. When the shame from that disappeared, my fatphobia started to unravel and I felt free.

Fat Moment #2: I stood up to a relative about their preoccupation with my fatness.

During a Zoom call, a well-meaning family member said to me,“Alia, if only you lost weight, you could really be something.” This was only weeks after I became a published author and heard news that my first film was green-lit for production by a major broadcaster. More than that, I was generally happy, despite the world seemingly being on the brink of collapse. By all accounts, I was thriving, but they couldn’t see past the weight. These kinds of comments are so commonplace that I have learned to grin and bear it, despite how damaging they have been to hear. But I had changed, instead of my usual silence, I opened my big fat mouth and said, “Your problem with my weight is yours to deal with, I don’t need or want to be constantly reminded that for whatever reason, you don’t like how I look.”

Knowing where my fatphobia ends and someone else’s begins has helped me be more precise in drawing hard boundaries to protect my energy. I have already wasted too much time on the narrative that my life really can only begin when I am an ‘After’, I am perfectly happy to live my life to the fullest now, on my own terms, in my Happily Ever Before.

Fat Moment #3: Took a selfie of my fat belly and put it on the internet for all to see.

A full year after Fat Moment #1, I was walking down the street, wearing a crop top (yea, I wear those now). I caught a glimpse of my belly reflecting in a store window and saw a batch of fresh new stretch marks. Another thing I felt was the complete absence of shame, a lack of anxiety and it was remarkable. I just said to myself, “Oh. New stretch marks.” and that was that, I was really proud of myself. That same day, I came across the AGO’s #PortraitsOfResistance, a project to “showcas[e] moments of emotion and resilience in everyday life.” I wanted to celebrate my moment of resilience. So I stood in front of the mirror and took a selfie of my belly. My heart pumping, I uploaded it onto the website with a description that reads, “a close up photo of the artist’s large belly”. There was absolutely no hiding the fact that this bulging belly belonged to me. I laughed a lot at my own audacity and felt very pleased with myself. There it was among many beautiful pieces of art; my belly. On the website of one of Canada’s biggest art institutions.

A few days later, I took it a step further and posted the same photo of my belly on Instagram with the story of what I did. I put myself in front of my friends and family, the people I had most wanted to hide my belly from. I wanted to make the statement that I didn’t care about what people thought of my body anymore. A close friend of mine commented on the photo, “years of work went into that.” He was joking, but he was not wrong. It may have taken just a few minutes for me to take a selfie and upload it onto the internet, but it took me years, so much emotional labour and a year and a half in isolation to build the capacity to do something like this.

With the world slowly opening back up, we are going to leave our cocoons and get back outside. I can already tell that the billion-dollar diet industry is gearing up to bombard people with messages that Fat is Bad. I know because I have spent more than one afternoon reporting diet ads on social media for harassment. The world is going to be mean-spirited about fatness again, and people will go back to policing my body. I can feel it coming.

Bring it on.

I did not live through a devastating global travesty, just for things to go back to the way it was before. I am declaring here that I own my experience with fatness. I write the narrative and I have decided that moving forward, my fatness will serve me, not shame me.

I’ve already started;

Fat Moment #4: Get paid to write an article titled “I Am A Fat Filipina And My Belly As A Piece of Art”

#TabachoyPower

(Tabachoy is ‘chubby’ or ‘fat’ in Tagalog.)

Alia Ceniza Rasul (she/her) is an award-winning Filipina storyteller based in Toronto. She is a member of the Tita Collective, a sisterhood of Filipina multidisciplinary artists. Additionally, she has recently published her first collection of poetry “Super Important Filipina Thoughts” which was included in CBC’s “55 Poetry Collections To Read This Spring”. You can find more of her work at aliarasul.com or on Instagram, @aliarasul

This story was selected as part of Shedoesthecity’s New Voices Fund, established to help continue offering opportunities to talented emerging writers with less than 20 bylines. More info here.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram