I read my own words; my own explanation of my life:

“Through my struggles with mental illness, I experienced life as an in-patient in a psych ward three times before the age of 18.”

My writing on mental health is extensive and open, but the words “psychiatric ward” carry with them such immense weight that they have the power to immediately alter the tone and focus of any piece. Often, even I question the acceptability of referring to this section of the hospital using that title— the term “psych ward” is so often used to misrepresent the place, at times it feels like I’m using a derogatory label against myself. Though… at the end of the hallway, there was a sign that read: “Sunnybrook Youth Psychiatric Ward”. I stared at that sign long enough that I”ll never forget it…

I should be able to share my experiences —because it is my truth. But should it be in my bio?

A biography is, after all, a curated presentation; an introduction to help people get to know you. It is a positive balance of personal and professional, so why would I include statements that highlight my struggles? As I asked myself that question today, I identified a few reasons that form the foundation that allows me to hold these words up with strength.

To Advocate for myself and others

Discussions about complex emotions and experiences should be acceptable in everyday situations, because these conversations help us become comfortable with their existence.

The struggles I faced in those times, as well as the struggles I witnessed others experience in the psych ward, were harrowing. I do not want to overwrite the truth of that fact by minimizing the dark nature of severe mental illness.

Mental illness is a dangerous truth, but It is important not to fear those who live with it. We must be open to accepting those whose actions seem distant from our own understanding – so distant that it is hard to associate feelings of “us” and “we” with an experience that, as a society, we’ve been taught to think is embarrassing. Even while we acknowledge the differences that distinguish us, we can always find the humanity in every person we encounter.

I missed prom while in a youth psych ward. I missed my high school graduation because I had only just left the hospital and had no idea how to talk to anyone in my grade. While others walked with confidence across that stage, proud of their past and excited about the future, I was learning how to see any possible future at all. I turned 18 while in the psych ward. I was an inpatient because I could not see a future where I could cope as an adult. I could not imagine a life without fear.

Normalizing the discussion of a topic as difficult as mental illness has also helped me normalize myself. By stating my experience loudly, I hope to help make it less of a big deal to openly discuss mental health in all its various forms.

For Freedom

I was separated from society for extended periods of time, but it is essential to me that the separation from society I experienced does not continue in the form of barriers in my interactions. One of the most challenging parts of leaving the psych ward was carrying the weight of its label out the door with me. I was in grade 12, and I had to learn to be proud of important parts of my past that I felt that I couldn’t bring up in regular conversation.

I have to be proud and accepting of my past in order to feel the strength of who I am today. Being open about my history with mental illness has given me the power to understand and better come to terms with it. By no means am I immune to worrying about discrimination. I experience moments every day where I fear that, by being truthful about my past, I am inviting negative assumptions about who I am and how I act. We all have awkward moments of regret about our behaviour, but when I have moments when I feel I’ve acted outside the norm, I have to worry about people thinking I’m “crazy” (a word that’s tossed around too flippantly), because of the information that I make available about myself.

For the shared and personal strength

I spend a huge amount of time fearing that my actions might be interpreted as the “not okay” type of weird. I wonder whether these anxieties would be less prominent if I chose not to disclose all of my struggles. But then I wonder if I’d be leading a life in constant terror that these “psych ward” facts would be discovered, made all the more shameful by my attempts to hide them.

Of course, I know many people DO choose to keep their in-patient experiences private. That is an understandable choice. I do not advocate for openness that could take away from your strength and feelings of safety. I write to advocate for acceptance so that, oen day, there will be no need for questions of safety when the topic of mental illness comes up.

To celebrate Pride and Personal Growth

I am proud of my response to having been a psych ward patient. I am proud of my hard work in regards to emotional intelligence, and I am proud of the grit I’ve had to show in facing my feelings. My ability to be proud of that time derives from my decision to share the details of that time. I am not proud to say I was a psych ward patient; I am proud because I am able to say I was a psych ward patient.

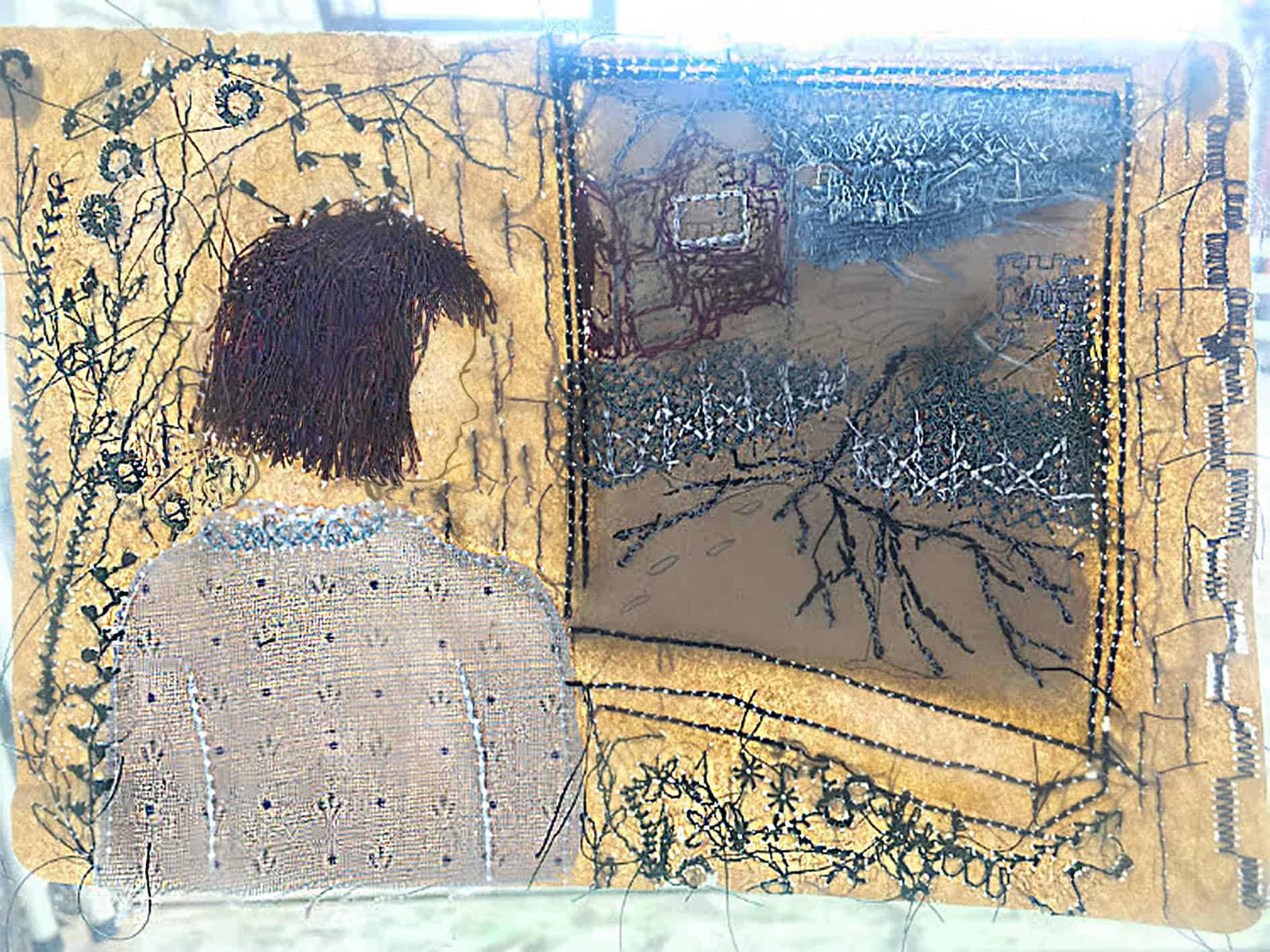

In the psych ward, I was silent. In the depths of my struggle, my emotions existed in chaos and I had no language to express them. I didn’t understand how words could possibly describe what I was feeling, so I grew increasingly inward. Promises of eventual progress (we’ve all heard “it will get better”, and felt the nothing it’s done for us) seemed like impossible lies. I ‘existed’ in a long-term state of all-encompassing hopelessness.

Something I recently heard sums up why I believe that some mental illnesses can begin to heal with hard work. In an interview with Brene Brown, Marc Brackett, author of Permission To Feel, discussed our responses when we believe we are not able. He used the example of a child that gives up on a creative project due to fears of criticism, and has no knowledge of how to deal with that: “…they give up, not because of their ability, but because of their inability to deal with their feelings.” This sentence means a lot to me, because this experience has existed to varying degrees throughout my life. There are large and obvious examples when I avoid situations that might make me think about things that I attribute to negative emotions, and less obvious examples, where I even avoid situations of positive emotion.

However, Dr. Brackett’s statement also resonates for me in an explosively massive truth: I had a complete inability to deal with my feelings. which left me in a place where I was convinced that my only option was to give up. Learning to deal with my feelings saved my life. What “dealing with feelings” can look like is, in part, the life-long learning of emotional expression.

Introducing “Me”

The ‘me’ I learned to like emerged through honest words. As I learned to let others see a hidden me, I began to see her too.

So, why is it that I want you to know I was in a psych ward?

To advocate for myself and for others.

For freedom.

For the shared and personal strength.

To celebrate the pride and the growth.

And, to introduce me to you.

“Through my struggles with mental illness, I experienced life as an in-patient in a psych ward three times before the age of 18.”

It remains in my bio.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram