In the past two years, I’ve had two major operations. One was a hysterectomy, and the other was to remove endometriosis on my nerves. My daily discomfort and deteriorating mental health created a negative atmosphere in the house. I couldn’t stop my grimaces of pain or need to retreat and lie down. All I wanted was to be free of pain so I could be an active and involved mother again.

I was acutely aware of my little girl in the background, watching my every move. Her eyes would often track me around the room to see if I was in pain. I was stressed out but prepared for my surgeries, however my young daughter wasn’t. I struggled with how to explain it to her in terms she would understand.

My daughter was five years old when I had my first operation. Since she is a highly sensitive child, I wanted to explain it to her, but at her level. My main goal was not to freak her out. Since she is prone to worry, I knew I had to be extra cautious.

First, I searched the internet to see if there were any kids’ books that could help. Eventually I stumbled upon a couple that matched my needs, like Why Does Mommy Hurt? by Elizabeth M. Christy, and Mommy Has to Stay in Bed by Annette Rivlin-Gutman. I promptly ordered them and introduced them into our nightly routine of reading books before bed.

Being a child of a parent who has chronic pain or mental illness is tough. I knew she probably had a lot of big emotions inside her that she didn’t know how to process. I didn’t want her to suffer quietly, so I decided to be as honest as I could, without making a major deal out of it.

One night as we cuddled in her bed, both of us in a relaxed state, I saw my opening.

“You know Mama has to go to the hospital soon, right?”

“But you don’t look sick,” she said, accusingly.

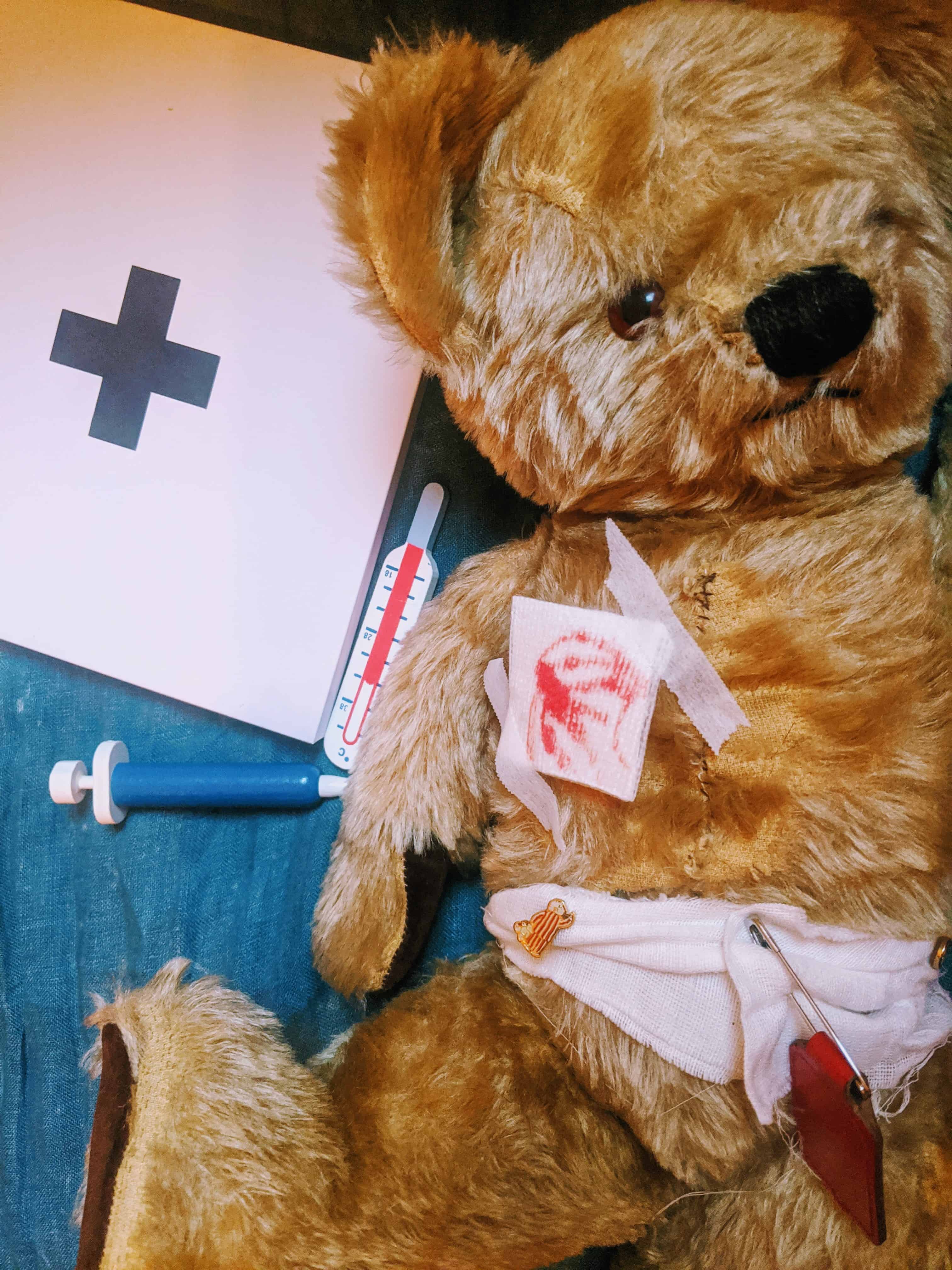

“Well, that’s because my pain is on the inside. It’s not like a scrape that you can put a bandage on. My tummy is hurting a lot. It’s invisible and you can’t see it, but I need a special doctor to fix it.”

“What about your pills?” she asked me. “Don’t they make it better?”

“Yes,” I answered her. “But the pain is getting bigger every day, and I want the doctor to take it away. The only place she can do this is at the hospital.”

I could feel her little body start to shake as she digested my words.

“But I don’t like hospitals!” she cried. “They smell funny, and all you see are old people.”

“I know they’re not your favourite place, but my doctor is going to fix me, so I can do fun things with you again, like dance parties and playing tag.”

There was a long silence.

“So you’re coming back?”

Hot tears filled my eyes when I realized her main fear was abandonment. I felt horrible for putting her in this situation, but this was our reality, and I needed her to understand as much as she could and be able to cope with it.

“Mama always comes back. You know that,” I said in a reassuring tone.

This had been my refrain during her preschool years, when she was afraid I wouldn’t pick her up.

“You know that, right? I always come back. I promise you: I’m going to be alright.”

She nodded again, popped her thumb in her mouth, and snuggled closer to me.

***

When I went in for surgery this year, my daughter was a year older—and wiser. She didn’t understand why I needed to go to the hospital again. Didn’t they fix me last time? Now she was angry about the logistics, and how long my recovery period would be.

“I don’t want to have a sleepover at Nana and Papa’s house!” she shouted.

“I know, but they need to look after you when I come home from the hospital the first night so I can rest. I’ll need to be in bed for a while, so I can get strong again.”

“Does that mean we can bring the TV upstairs and watch Netflix, like last time?” she asked.

“Definitely. And we can also eat a huge bowl of popcorn.”

Her face lit up at this news and I let out the breath I’d been holding, afraid she’d be overwhelmed with the trauma of her mom going into the hospital again. I knew my husband would also help make my recovery smoother so I could heal and still bond with her at the same time. He would bring up board games we could play in bed.

Being my “special helper” also made my daughter feel more powerful and useful. I hope I never have to experience that pain or this conversation with her again, but if I do, I feel confident that we’ll both be able to handle it.

Tara Mandarano is a Best of the Net–nominated writer and editor, and an advocate for patients in the mental health and chronic illness communities. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram @taramandarano.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram