The bus rolled into a small town in rural Tanzania as the sun was setting. Being close to the equator, the sun rises and sets quickly, and there was little time before it would be dark.

“What town am I in?” I asked somebody as the bus stopped at the side of the road. After a short conversation with my neighbour on the bus, I realized with a sinking feeling that I was not in the town I was expecting to arrive in. Apparently, buses don’t go there anymore. I had no idea where I was, no idea where this rural village was, and no idea what my next step was in the journey to my final destination: Gombe National Park.

What followed was a four-day misadventure with at least as many buses. I had been working with a community of Congolese refugees in Kampala, Uganda, and had dedicated time after my work was done for a personal journey. A pilgrimage. I was travelling to Gombe, the place where my hero Jane Goodall had carried out her landmark research into the lives of chimpanzees. Her seminal work In the Shadow of Man was in my bag, along with a cheap camera, a few rolls of film and a stack of journals. I was 22 years old and, as was my custom, I was travelling alone.

Our first breakdown happened thirty minutes after departure, still in the outskirts of Kampala. Flat tires and mechanical issues were a regular occurrence, with one particularly notable breakdown leaving us standing in the midday heat in a people-less, desolate stretch of baked earth. My days consisted of eight- to seventeen-hour bus rides with no stops for food or washroom breaks. Lengthy delays meant that I would miss the ferry to Mwanza, and so I cobbled together a meandering path of supposed buses that mostly existed only on paper.

Completely lost and at the mercy of the fluid Tanzanian bus system, I relied on kind strangers for help. What town am I in? Where can I stay the night? Where do I catch a bus tomorrow, and where will it go? The unanswerable question: Why does that bus no longer exist? People were kind, and information was scarce. The buses were crowded with passengers of all strokes: people and chickens were cheek to beak. Massive bags of fish were transported in the aisles of the bus, and three or four rear ends occupied a seat for two. To move throughout the bus, you simply climbed over adults, babies, live chicken and dead fish. As we neared villages and towns, you could buy fruit, bread and biscuits through the bus window, and I filled my belly with a diet of oranges and wafers.

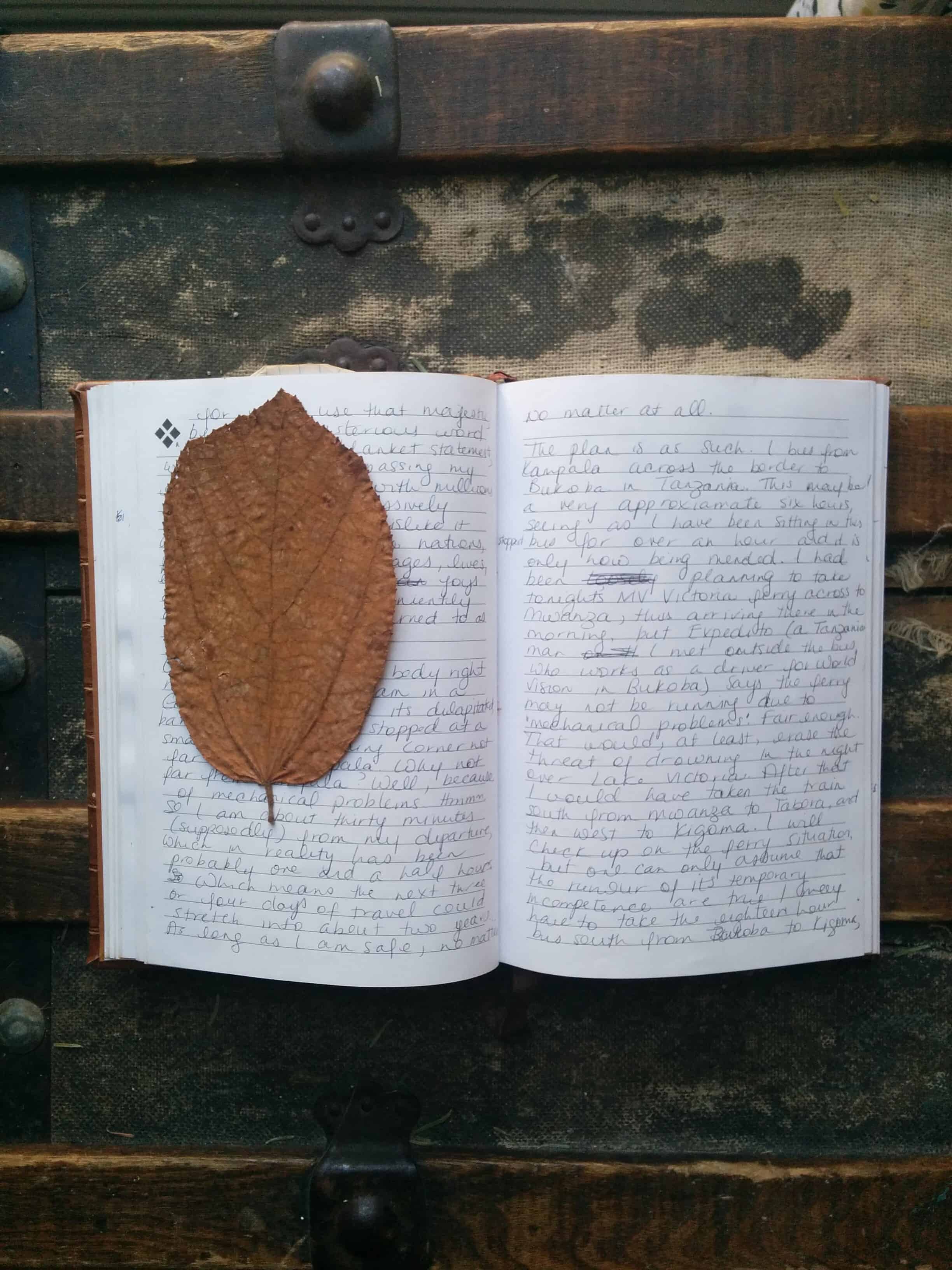

Pages of my journals are filled with jagged, bumpy writing: “Wait – the bus just dieseled its way to life! Hmmm, it shudders but it does not move. Curious and none too encouraging.” And, “Every time we stop, more people sardine in, but no one ever gets off.” There was a surprise ferry that I found myself at some point; there was a time when passengers spent a half hour piling rocks under the tires as a truck, attached by rope to our fabulous bus, pulled it loose from whence it was stuck. The bus rumbled on in all its glory. We would stop for the night and I would find a bed wherever we rolled in, quickly before the sunset. The final day was a seventeen-hour slog that followed the exact route I had been trying to avoid, a purportedly dangerous route from Bukoba to Kigoma along the Congolese border that Lonely Planet candidly and accurately refers to as hell.

At last, I arrived in Kigoma. Exhausted, I was covered in bruises from being squished and stepped on. My bag and everything in it was covered with red earth from the great underbelly of the bus, and when I rinsed my hair with cold water, orange rivulets slipped down the drain. But here I was, in Kigoma, closer than ever to Gombe. I slept mercifully for the night, and then found the shore of Lake Tanganyika in the morning. I bartered with some gentlemen to secure my spot on a massive lake taxi, which would bring me to Gombe in three hours, perched on the gunnel of the boat.

Gombe was a transformative experience in my life. It is the most beautiful place on earth. Soaring forest covers the hills that are rooted in Lake Tanganyika. My first sights of the lake were of its expansive waters under a wavering setting sun in a peach sky. The distant mountains and hills of the Democratic Republic of Congo were misty and blue-green. I felt as though I were being swallowed up by the grand landscape, in the best possible way.

Walking through the forest was peace incarnate. You could hear birds and snapping twigs and, yes, chimpanzees. With the expert help of a guide, I had the incomparable experience of walking behind a family of three chimpanzees. The unfazed mother ambled along through the forest as her infant ran excitedly with the energy of youth. The young one would grab onto trees and swing around them as the mother continued on with the regularity of a metronome. A second, older child was more independent and strayed further from her mother and sibling, but never went too far. The differences between this family of chimpanzees and a human mother, baby and teenager were scarce. The mother cast a few unimpressed glances my way, but seemed mostly indifferent to my human presence. I followed them around trees, under thicker brush and past a magical waterfall that stretched up vertically above us.

At night, I was invited into the cabin where my idol Dr. Goodall had lived while conducting her research in the forest. This is where she came in her mid-twenties on a six-month contract to learn more about humankind’s closest living relative, the chimpanzee. Over fifty years of unbroken research has continued here ever since. It was here that she gathered findings that shook the scientific world, including a discovery that humans are not the only species to make and use tools. The research conducted here fills her countless books and has inspired generations of people. The individual chimpanzees that lived in these hills over the decades were known to me, through the captivating words in Jane’s books and speeches.

Ever the nerdy fan, I felt breathless to be there. Anthony Collins, the director of baboon research at Gombe, sat with me over dinner and our conversations stretched on. During a particularly exciting interaction, baboons leapt at, over and around the cabin in a flurry, and Dr. Collins expertly described what they were doing. I learned, listened, soaked it all in.

All of this, however, was not what changed my worldview. There were only two Westerners there, yes, but nevertheless I was a visitor. What was truly transformative about being in Gombe was a shift in mindset that I have carried with me ever since. Close to the end of my time there, I met a young man from the area that told me about Roots and Shoots, Jane’s youth program that inspires and supports young people to get involved in their own environment. From that point forward, I learned about a development philosophy embraced by Jane Goodall and her Institute, which looks at animal conservation, environmental preservation and reduction of poverty holistically. At the time, this was not mainstream thinking, and it affected me deeply. How can you tell someone who is living in poverty not to cut down the last tree to feed their family?

It is only in retrospect that I realize how profoundly this affected me. Two years after that landmark visit to Gombe, I founded Mother Nature Partnership, an organization that was born out of a question: how do we look at environmental action and women’s rights holistically? What can happen at that intersection, between women and their environment? The idea struck me: through reusable menstrual health supplies and information, girls and women can respect the environment and their own bodies. Equipped with environmentally conscious menstrual cups and pads, they are free to attend school, go to work and live life fully. Until recently, I didn’t see the connection between Jane Goodall’s holistic philosophy, and my own path to being an advocate at that interconnection between women and the environment.

Dr. Goodall long ago stopped being solely a chimpanzee researcher. She became an activist. She is on the road three hundred days a year. Across Canada this week, this indomitable 82 year old is speaking with her devoted public – as well as Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, government and the media – about her message for environmental action. She is outspoken, articulate and funny. Most of all, she is still hopeful.

Just as she was controversial in her early days of research – when she gave her research subjects names, and ascribed emotions to our brethren from another species – so too is her approach still radical today. She talks about the interconnectedness between animals, people and the environment. Humans are a part of, and not above, the rest of creation. Species are not a matter of different kinds; it is a spectrum. The brain and the heart must work in concert, and too often today we are letting these two entities fracture from one another, with the brain doing all of the talking. She insists that there is still hope, for the species we inhabit this planet with, for Mother Earth, and for us. Every one of us makes a difference every day, she told three thousand people at the Sony Centre on Tuesday night. It is up to us to determine what that impact looks like.

After she finished her powerful lecture and the standing ovation was over, I had the great fortune of meeting Jane Goodall in her dressing room. There she was. Her words of advice still lingered in my mind: don’t worry about making a mark. Take time to figure out what your passion is, and work hard and pursue it relentlessly. Maybe then you will make a mark. I handed her a letter that I had written hastily in the seats of the auditorium as the lights dimmed before her lecture. It was stuffed into an envelope with a few photographs I had taken in her beloved Gombe, nearly a decade ago.

As she looked at me and said, “It is nice to meet you.” I felt less like I was standing in her shadow, and more as though I were standing in her light.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram