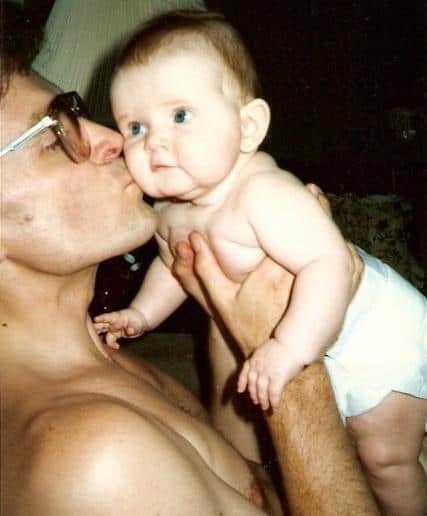

My Dad died.

That phrase comes more naturally to me than most others. I’ve said it countless times over the past year. I started to practise saying it before he passed away, so I could present the words without any thought or feeling behind them. “My Dad died.” Those words describe everything and nothing of what has happened. Those words mean nothing to me now.

Diagnosed with a terminal brain tumor and devastated by an awareness of the severe, increasing loss of his faculties, my dad tried to kill himself on Thanksgiving. He slit his left wrist with a paring knife and sat in the bath with his housecoat on waiting to die. We spent fourteen hours in the emergency room with a guard standing outside of the door to make sure he didn’t pull a Houdini before they admitted him to the psychiatric ward for ten days. A too-nice nurse asked, while sewing up his wrist, why he tried to end his life. “Because I’m dying. I’m finished.” Would he try it again? “Yes.” He died one month later.

I’ve heard and used the word “grieving” so many times over the last year that I have come to loathe its inability to pinpoint what it is, exactly, that I’ve been doing. I used an online thesaurus to see if I could find a more apt word to describe what it feels like to know that you will never have another conversation with your favourite person, and the list is pretty long. Grief is quite simply all of these words and none of these words.

I used to take great comfort in the knowledge that everyone will or already has gone through what I have. I don’t really feel that way anymore. Now I feel like mortality is a big elephant in the room that we’re all trying to nimbly and quietly ease ourselves around. Dealing with grief in quiet exile from the functioning world, I have often felt disappointed that we don’t view the grieving process as a source of communion in our society. I don’t know that I have ever felt anything but aloneness during my experience.

So many people have a well-intentioned, but nonetheless, flippant way of dismissing serious problems by telling you that “everything will be fine,” when mostly what is needed is for someone, anyone to acknowledge that what is happening is real and difficult. Denying reality because it is easier than having an honest conversation is extremely isolating, for both parties.

My Dad’s diagnosis came with a life expectancy of eighteen months. He lived for five. I had hope the whole time, but I did know that he would die. As his body began to deteriorate and the brain tumor irreversibly altered his personality, the tenacity and perseverance he was once able to conjure in himself and inspire in others was snuffed out and replaced with despair. The clear-sighted man I once knew was outwitted by his own ailments. Statements from friends and peers like, “I had a friend who had cancer, and she beat it!” only served to further separate my reality from theirs. I kept most of my experience private, allotting myself fifteen minute intervals to cry and pull myself together in the bathroom at work.

For me, the loss of my father has been exhausting, physically and emotionally. Grief is a full-time job. I have watched with frustration as my body slowed down against my will. My memory is not very good. I am often alone with my thoughts in a room full of people. I have lost many friends who were close to me because the divide between what I’m constantly replaying in my mind and the mundane topics we discuss feels too overwhelming. I am desperate to bridge that divide and to let it gape wider, grow cavernous. I want everyone to rally around me and to stay as far away from me as possible. I want you to ask me how I am and I want you to pretend like nothing ever happened.

“Is everything okay?”

“I’m just very tired today.”

Grieving means struggling to control feelings that do not seem mine to control. The difference between grieving and regular sadness has been the inability to change my emotions by changing my perspective. There are good days, when I have the kind of energy that I had a year and a half ago and I am in awe of what I am able to achieve with ease, but inevitably, without warning or notice, this energy disappears as quickly as it came and I am laid out flat on my back by a memory or a smell, or worse—a newfound realization of what has happened.

I have always wanted, badly, to believe that there is sense and order in the world, that there is a lesson to learn from suffering. But grief feels like a gaping, aching hole in my solar plexus. Everything good that happens is poured into an entirely clichéd abyss and disappears because I cannot share it with my Dad. I often fear that I will never find joy in the same way that I once did.

I spent a few hours alone with my Dad one afternoon, shortly after he was admitted to the hospital. He was sleeping, and there was no comfortable place to sit, so I lay my head down at the foot of his bed and slept hunched over, using my arms as pillows. When I woke up to leave he was awake. As I was on my way out the door he called, “Keep yourself happy.”

I will.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram