Just who is Elaine May? A comedian, screenwriter, and 1970s Hollywood director whose bold, uncompromising films were often railroaded by male industry execs. Until now.

Funny Girl: The Films of Elaine May runs next month at TIFF Bell Lightbox. This funny and poignant retrospective will include The Heartbreak Kid, A New Leaf, Mikey and Nicky and more. We chatted with curator Alicia Fletcher about why she programmed this series for TIFF Cinematheque, and why now, more than ever, we need some Elaine May in our lives.

SDTC: What was the most interesting thing you learned about Elaine May in putting this retrospective together?

AF: I was aware of May’s notoriety going into the retrospective, but researching the exact play-by-plays of her studio manipulations was illuminating. In some cases, they read like calculated maneuvers between warring nations. Each of the four films she directed were struggles—struggles that came to a crescendo with Ishtar; however, it was an anecdote from the production of her criminally under-appreciated Mikey and Nicky—a film released by Paramount in 1976, starring Peter Falk and John Cassavetes—that made May stand out for me as the preeminent Hollywood badass.

In typical fashion, May went over budget and over schedule, yet Mikey and Nicky was more egregious. She shot more footage than Gone with the Wind, rolling the camera long after the principal actors had left the set. And while she was accused of wastefulness, it was clearly part of her process—almost like a documentarian—and the film benefitted from this dedicated approach.

When Paramount fired her as director and looked to replace her, she nonchalantly hid two reels of the negative—effectively holding the studio hostage—until they gave in to her demands that she be reinstated and finish the film.

Bold, brash and unrelenting—how May ever fit into Hollywood is baffling, although I think it was more an issue of Hollywood fitting into May. In researching May, multiple instances arise where she is painted as a sort of freedom fighter, an insurgent, or a revolutionary, acting against Hollywood’s narrow-mindedness.

Mikey and Nicky

What makes her films essential viewing, in your opinion?

Simply put: they are so damn funny–funnier than any film from the immediate aftermath of the studio era has a right to be. May’s distinct brand of comedy feels wholly unique and went on to influence icons like Steve Martin, Lily Tomlin and Bill Murray.

She could draw out the most acerbic, cringe-worthy performances from men—existing comic icons like Walter Matthau (A New Leaf) were seemingly and impossibly improved by her. She could transform bonafide matinée idols like Warren Beatty into laughable duds (Ishtar). And she could shape and mould the future careers of young comedians in their earliest roles, as she did for Charles Grodin in The Heartbreak Kid.

No one was really doing what May was doing at that point in the industry. It’s not just that she was a pioneer or vanguard (and she certainly was that); it’s that she made films on her own terms, or at least she tried to, with varying degrees of success. She’s so funny that it’s almost tragic, which is a metaphor for her career. Were she not blacklisted and lowballed by Hollywood, her films would be better known. Were she a man, her relatively minor slip-ups would have been forgiven—Spielberg made 1941, after all.

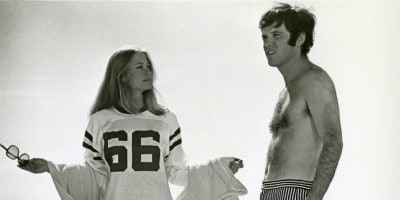

The Heartbreak Kid

What is your fave film by May, and why?

A New Leaf, her directorial debut from 1971. Walter Matthau stars as a spoiled playboy who, after squandering his inheritance, sets out to woo and marry a clumsy heiress…then kill her (or at least try to in a series of sinister shenanigans). The heiress, a clumsy botanist, is played by May herself, and it is, for me, one of the great characters of 1970s American cinema.

It’s also one of Matthau’s top performances and sees him act against type. I feel slightly remiss stating this as my fave, as in the end, May disowned it after she lost a lawsuit with Paramount for final cut. Regardless, it’s perverse yet sweet. Funny yet deeply unsettling. Lighthearted yet dark. It embodies all the contradictions that I love in May’s filmmaking. It’s also super stylish and I love her character’s ridiculous costumes—I’ll forever picture Elaine May in an ill-fitting hat when I think of a botanist.

What was your first exposure to her films, and how has your perspective on her work shifted over time?

Her films were (and in some cases still are) notoriously difficult to procure. There’s a terrible quality, borderline unwatchable DVD of The Heartbreak Kid, and no studio restoration in the works. 35mm prints of that title are treated like the Holy Grail—treasured, protected, possibly guarded by Teutonic knights. The print we’re showing is being flown in from Sweden (complete with Swedish subtitles).

Outside of Ishtar, which I knew by reputation, I could acknowledge her by name only until relatively recently. Her name was frequently dropped as a pioneering filmmaker in my film education, but there were few opportunities to see the films she directed. I think many have been exposed to her screenwriting without realizing it. In The Birdcage, for instance, Heaven Can Wait, or Tootsie, she served as a crucial but uncredited script doctor. At one point, I contemplated naming the retrospective, “Uncredited and Undervalued: The Films of Elaine May.” It’s 2018 and there’s no substantial written biography on May. There’s a litany of written material on her former improv partner and longtime collaborator, Mike Nichols, but researching her proved tough—partially because she recently admitted in an interview to fabricating much of her origin story (another May twist that I love)!

In light of #MeToo and the massive shifts in the entertainment industry, why is it important we see her films now?

Recently, there’s been much discussion of how men have ruined the promising careers of women in the industry through blacklisting and underhanded tactics of intimidation. We can only imagine what May must have seen in the 1970s and 1980s. She was in such a unique position then–a woman in charge–yet, in her desire to make the films she wanted, the way she wanted, she brushed up against Hollywood suits and this led to her being blacklisted from directing. It’s one of the major injustices in Hollywood history. May was specifically brought on to improve the script of Tootsie by imparting a deeper understanding of what actresses had to deal with in the industry—sexual harassment was a major part of that. While her work on Tootsie went uncredited, I feel that May’s voice is very much there.

Heaven Can Wait

How would you describe her style of filmmaking to someone who has never seen her films?

The 1930s screwball comedies of Howard Hawks mixed with the deadpan humour of Harold and Maude, with a dash of Larry David. A May film elicits deep laughter, but it’s a kind of laughter that leaves you grimacing. It’s a biting humour and it hits hard at the hypocrisy of patriarchy and class.

In the end, her characters—even the ones you are encouraged to loathe—are exceptionally relatable. Some of her greatest comic moments remind me of those terrible nights when you can’t sleep and you inventory every humiliation you’ve experienced in your life. I think May knows how to turn that kind of self-pity into comic gold, which is why her films still resonate today.

Funny Girl: The Films of Elaine May runs June 8 to 30 at TIFF Bell Lightbox. Get tickets here.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram