My Sister’s Closet is a social enterprise of Battered Women’s Support Services (BWSS) and a shining example of what can be achieved when we put people before profits, and prioritize sustainability.

In 2020, BWSS responded to 32,000 requests for service—up from 18,000 the year before. With 100% of its revenues going towards funding BWSS’s life-saving programs and services, My Sister’s Closet has been instrumental in supporting thousands of victims and survivors every year—and this year is their 20th anniversary. The work they do is invaluable, and over the past two decades they’ve supported hundreds of thousands of women.

There are two brick and mortar locations in Vancouver run by approximately 50 volunteers, as well as an online shop. The East Vancouver shop is located at 1830 Commercial Drive, and the Downtown Vancouver shop is located at 1092 Seymour Street. At both locations you can donate gently used clothing and shop preloved clothing. The shop also helps get clothing to women in need, and last year supplied approximate 500 people with free donated clothing. Further, both locations also put the issue of systemic gender-based violence at the forefront, raising awareness, providing education, and acting as safe spaces for community members.

Inspired by the success story of this social enterprise, we connected with Angela Marie MacDougall, Executive Director of Battered Women’s Support Services.

When it comes to violence against women, what has changed in 20 years, and what remains the same?

The biggest change is that we have more awareness now about prevalence and how much of an epidemic violence against women and gender-based violence is. That change has been compounding over the years, but it really has happened as a result of the various kinds of hashtags that we’ve had, #RapedAndNeverReported, for instance, as well as #MeToo.

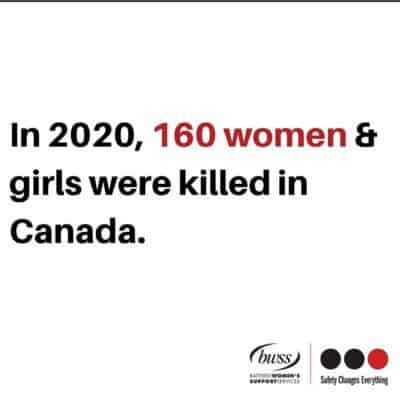

Up until fairly recently, gender-based violence has not been thought of as being systemic. Each case or each femicide, each killing, is treated as a one-off. So what we have now is a broader sense across the broader population about the prevalence. And that also had to do COVID-19 and the amount of attention that was placed on the kind of precarity there would be for victims who would be co-quarantining with their abusive partners.

The other thing that has changed is there are increasingly more services. Now, it’s not nearly enough, but we have more services and that’s been a 40-year budget advocacy for feminists, primarily, in order to have government funding and other funding to ensure that we have a matrix of services that meet survivors at various places in their journey. The major thing that we don’t have, which we continue to seek, is the broader social change that would be at the heart and the root of the problem. I mean, when we see young people emerging in the dating scene, sexual violence continues unabated. Intimate partner violence continues at rates that have been not unlike other generations. So the broader social change has yet to be realized, and that’s what we continue to work for.

You received 18,000 more requests for help in 2020. What conclusions have you drawn from this?

The biggest conclusion, I think, is that we did really well in getting the word out about what it was going to mean to be under COVID-19. Every time there was a media story, the calls would spike and that’s what we recognize is so important: that survivors/victims need to know where their services are and how to access them, and the services need to be available when the survivor calls.

And I’m talking about community-based response, not what would be maybe the police response. That criminal piece, if there are going to be charges or anything, is really just a small part of the survivor’s life. What is most impactful is the community-based response. And so that’s what we’ve been really wanting to highlight and to emphasize, the necessity for that community based response and to continue funding it.

The other important piece that we recognize is that the community does care. I mean, in general, the community cares about gender-based violence. This is why we continue doing the work, to continue to try and fill these gaps the best that we can.

My Sister’s Closet is turning 20, some people might assume it’s just a clothing store – what do you want to tell them?

The biggest thing about My Sister’s Closet is how important it’s been as a brick and mortar location for people that want to interface with the issue of gender-based violence, but also for issues around the environment. Fabric is second to oil or gas as the biggest polluter in contemporary times. Our work is to raise awareness around violence against women, but also about fast fashion and sustainable fashion, while wanting to continue to build a broader-based community that is thinking, seeking, and wanting to begin to slowly weaning ourselves off fast fashion and investing in pieces that are more sustainable

Can you share the kind of programs that sales from My Sister’s Closet supports?

The biggest support that we’ve needed this year was around the crisis line and moved it from a daytime line to a 24-7 line. That’s been the biggest shift for us in what My Sister’s Closet funds. And the crisis line has made it possible for us to respond to just under 32,000 requests last year. The crisis line is often the first point of contact, and going 24-7 has been incredibly important.

The other important program that My Sister’s Closet funds is the Youth Ending Violence Program, which is violence prevention. This program is unfunded by any other source, and the primary funds come from My Sister’s Closet. This is dating violence education, and we have a wonderful youth worker who is in high schools, community centres, alternative schools, and private schools to bring a message around healthy relationships and consent and speaking with young people and also training young people to deliver workshops and to build a youth energy around ending dating violence.

The other piece is also a type of intervention: our outreach program. My Sister’s Closet funds that program, which has us on the streets in four neighbourhoods in Vancouver, five nights a week—reaching out to survivors who are dealing with violence, potentially, and having a visible presence on the streets. And of course, this is not new, but COVID perhaps made it more visible to many people, was the amount of sexualized violence that women and girls deal with just on a daily basis in terms of harassment, groping, those kinds of things.

Why is the location of the downtown store significant? What does it represent to you?

When we decided to expand to a second location, we were looking at neighbourhoods, and at the time Helmcken and Seymour Streets were a place where street based sex workers worked. We knew about a woman named Elaine Allenbach, who was a sex worker who worked at that corner across the street, actually, from where My Sister’s Closet is. She went missing in 1986 and there’s been no information about what happened to her. And so we thought was that it was important, in light of the amount of missing women that went missing during the 80s and 90s and the 2000s in Vancouver, to have a presence on that corner with the spirit of safety for women, for sex workers, about ending violence against women. We wanted to have that space, that energy on that corner and a presence there for that reason. And we don’t tend to make it very visible, but Elaine’s disappearance is very much on our minds and it is the reason why we’re at that intersection.

What do you want to say to the woman reading this in an abusive relationship?

We want women to know that there are options for safety and that it takes time to navigate an abusive relationship, and recognizing that everybody is on their own journey and at their own pace. One of the things that is so important is that, for so many women with abusive partners and in abusive relationships, they want the abuse to stop but not the relationship to end. And that’s such an important reality. We have a whole range of services and individuals that work with Battered Women’s Support Services that can support any woman wherever she’s at in her journey and thinking through what it means to be safe and what she wants in her life, and what are the challenges in her life that are compounded by an abusive relationship.

The main thing is that you’re not alone at all and that there have been thousands of women that have reached out over the years and that everyone has the right to be safe and to realize her dreams for her and her children, if she has children. And that BWSS can be a resource for her, at any point in her journey, and can really bring in a whole number of support options that can follow her through as long as she wants: including counselling, including support groups, including legal advocacy, including help with employment and a whole bunch of other supports that are very specialized and can be uniquely tailored to her.

If you are a woman experiencing violence in Vancouver and want to speak to a support worker, the crisis and intake line is 604.687.1867, or toll free at 1.855.687.1868. If you are in crisis in other parts of Canada, here is a link to organizations in each province that can help.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram