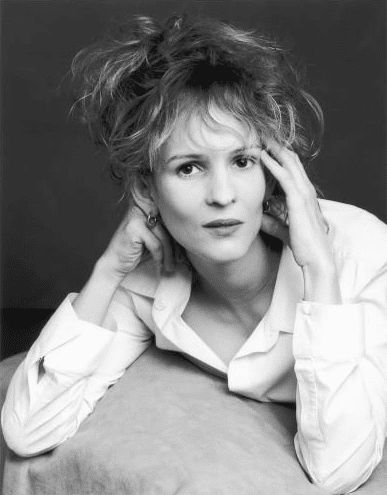

We’re pretty huge Tabatha Southey fans at SDTC HQ. Between her weekly funnies in the Globe and Mail, her kid’s book, her gone-but-not-forgotten column at Elle Canada, and her fantastic Twitter, we continue to read, share, and love her work. We caught up with the columnist via email for life/work advice, a glimpse into a day in the life of Tabatha, and some thoughts on the most subversive thing a woman can be.

SDTC: To start us off, can we get some background info—where did you grow up and go to school? How long have you lived in Toronto?

Tabatha Southey: I was born in Vancouver to parents ten-months immigrated from South Africa (my mother) and Zimbabwe (my dad). I’m an anchor baby, dragged many times across the country and sometimes to other countries, but I was raised mostly in Guelph. I moved to Toronto when I turned sixteen in the hopes (faint as it turn out) of finishing high school beyond the grade nine level I had so far, barely, achieved and (this still surprises me) I became a columnist for The Globe and Mail.

Tell us a little about your day-to-day work life. What does a typical Monday look like for you?

On Mondays I do the things that must be done that I’d rather not do—like meetings and lunch-y stuff, because I work intensely until at least Thursday when I file. Sometimes later— if a story is in flux or breaks late in the week. I remain available for last minute edits until my column goes to print on Friday. My name’s on it. I pay attention.

I read a lot, news and otherwise. There’s nothing very exciting about writing. As the mother in the British kitchen sink drama “A Taste of Honey” says when her young pregnant-by-a-departed-sailor daughter asks her about giving birth to a baby “Does it hurt, mum?” I would say, in a Northern accent, if I could, “It’s mostly just a lot of hard work.”

I track news stories. Because I’m a humour writer, most of my columns require a premise, a hook, and sometimes many ideas must be tried before, if I’m lucky, something works. No matter how absurd the angle I eventually choose may be, I won’t write on a news story if I don’t feel I have a pretty thorough grasp of the subject at hand: you can joke about any subject but a joke made from a perspective of genuine ignorance will never be funny.

What was your first-ever job? How did you get it?

I had a paper route. I got it by asking for it. After I moved to Toronto I worked a lot of different jobs, often at the same time. I worked as a nanny, a waitress, in retail, sometimes I’d model hair shows—getting my hair cut for money. It just got shorter and shorter and shorter.

When did you know you wanted to be a writer? How did you start?

Reading was close to being everything to me as a child. Reading was so important to me that the idea of being a writer seemed, and sometimes still does seem, presumptuous: being raised in a church doesn’t usually make you think you get to be God.

I did not begin writing, really, until I was about twenty-three, after my first child was born. To be honest, while I’d done alright in retail and was a serviceable enough server and there is no real skill to getting your haircut so I could do that, I had failed school spectacularly (beginning with kindergarten) as a child and the sense of my own incompetence that gave me had very much stayed with me.

Until I had a baby I’d never felt I was good at anything but when I found I was good at taking care of my baby, I began to wonder what else I could do. I’d always been a talker, surrounded by some great talkers, and soon after finding myself suddenly single and alone with a two-year-old and a newborn to secure my isolation I began to write down the things I would once have said aloud. I was then pushed and bullied into writing professionally—kicking and deferring and apologizing the whole way—by a women I met through my child’s nursery school and the woman to whom she introduced me.

Following up on name provide by one of these two women, I published a children’s book that I hoped would secure me a safe, quiet spot reading to children on the floor’s of public libraries for the rest of my life. However this same woman was hired at the newly launched National Post and kept insisting I should write for them. I love newspapers (read three a day cover to cover in the slow hours of my retail jobs) and I didn’t imagine I’d really be let in, so to speak, but I’d written a little joke-column-pitch down and eventually I sent it to her.

The idea behind the pitch was that the only thing my previous life (I’d been married to an actor) qualified me to do was write something like the old “Dinner Date” celebrity profile column the Toronto Star used to run in the back of their TV guide: If there was one thing I knew I could do, it was go out, eat dinner, pretend to be interested in your career and get a recipe. I said I’d like to write a column called “Drunk With Men.” The National Post ran my pitch as written but with no “fucks,” let me sit in on Weekend Post story meetings and published everything I wrote for the next two years. That was my J school, those meetings, and I’m incredibly grateful.

What’s the best piece of work advice you’ve ever been given?

Either “Ask yourself ‘Is it of use to the reader” or “If you want editors to like you always include a subject line in your email.”

What do you do when you’re not working?

Even once I’ve filed, there’s always more writing to be done. I also read, walk my dog, Tulip, cook for friends and I swim almost ever day, something so vital to my piece of mind, I consider to be part of my writing.

Do you have any writing rituals, a place you prefer to work or a power drink you consume on a deadline?

No, it’s writing, not sorcery.

What advice would you give to women hoping to start a writing career?

Write all the things, but learn one thing. Learn fashion, or politics, or wine, or cars, or books, or music, or tech. You don’t have to only write on that subject (but aim to be the go-to girl on that subject) and don’t let that subject be what it is to be a woman. Be prepared to encounter and counter the notion that what it is like to have a vagina is all a woman can ever tell a man.

This is not to say that personal writing cannot be done artfully and I think having a vagina is great, but a career about having a vagina won’t have legs and (despite what desperate-to-reality-TVize-their-lists publishers and click bait dicks will tell you) confessing is not breaking ground for women. “I’ve been a bad girl” is exhausted terrain (True Confessions magazine had a circulation of two million in 1930s) and its neighbour, the Land of Victimization, is over-farmed as well.

The most subversive thing a woman can be is happy, now get to it.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram