Pickup artists—once relegated to shadowy corners of the Internet—have reached the mainstream. Popularized by Neil Strauss’ The Game, this movement has been fomenting since the 1980s, spawning a worldwide billion-dollar industry. The Pickup Game, opening at Hot Docs later this month, is an incisive view into a world where students shell out thousands to self-styled pickup instructors in order to learn “game” (a calculated system to get women into bed).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MqpBkRd5A7E

Co-director Matthew O’Connor first learned of this phenomenon when his friend was hired to be a conversation girl at a pickup seminar. “Students who were there would listen to the instructors, learn the theories, and she would go up on the stage and they could practice those techniques with her,” says O’Connor. “I’d never heard of anything like that. She ended up dating one of the students for a while, but she said it was quite difficult because she was aware of some of the game-playing techniques… It was very hard to know when he was being genuine with her.”

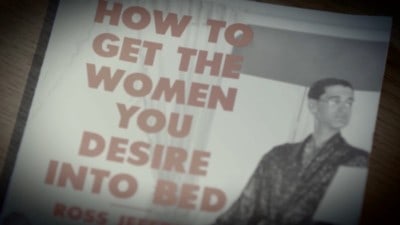

The film offers unprecedented access to these workshops and seminars, and it includes candid interviews with Erik von Markovik (a.k.a. Mystery), Paul Janka, Robert Beck, Justin Wayne, Maximilian Berger, and the guy who started it all, Ross Jeffries. “Initially, when you meet the people that run these courses, the argument that they make is ‘Well, we’re just helping guys gain confidence and giving them some techniques to help them meet women and not be so shy and awkward,” says O’Connor. “But as you get into it a bit more, all of that starts to unravel.”

Practitioners of game use a combo of alpha male posturing and aggressive sales techniques to seal the deal. Codified language serves as a shorthand for tactics and approaches; the woman being hit on is the “target,” and LMR is “Last-Minute Resistance” (when she rebuffs a sexual advance). Men are encouraged to write field reports of their interactions in order for other students to learn from their experiences. Often, unsuspecting women will be filmed while they are being approached, laughing nervously while the man presses on. “There’s a dark side, there really is,” says Minnie Lane, a dating coach featured in the film who is well acquainted with the PUA mentality. “I never thought that a girl could be tricked and manipulated into bed. But the evidence is there that actually, they can be.”

O’Connor attributes some of the popularity of this subculture to the rabbit hole of the Internet. You start watching one YouTube video about how to talk to women, and one thing leads to another. “It becomes a self-feeding echo chamber,” he says. “If you’re inside one of those, it’s easy to get lost.” But there is a common thread across all of these subcultures whether they be PUAs, MRAs, incels or white nationalists: Entitlement. “There’s crossover [between these subcultures] in terms of the kind of people who gravitate to that sort of thing, where they’re at in their life and how they feel,” says O’Connor. “A lot of these subcultures have similar narratives of victim wronged by society, mainstream lies to you, we’ve got the truth; [it’s] this idea of providing a brotherhood. It’s an outlet for frustration.”

But the online world has an insidious way of creeping into real life, sometimes with horrific consequences. “Toronto,” says O’Connor, “has a huge pickup scene. It’s one of the epicentres of it.” Through this film, he hopes to raise awareness of pickup so that women can spot these tactics early on. “A lot of the pickup mentality is sales, essentially,” says O’Connor. “Pressuring people into being in situations that they wouldn’t necessarily find themselves in. [One tactic] is instead of saying, ‘Do you want to come back to mine?’ they’ll say, ‘Do you want to go get an ice cream?’ and they walk the girl to their apartment. Obviously, that can put women in a situation where they feel pressured. We want to raise awareness of that side of things.”

“This is a business,” says O’Connor. “These guys are in it for the money. They say they’re helping people, but they’re making a lot of money. It’s not truly altruistic.” Throughout filming, O’Connor found it difficult to understand how much these instructors believed what they were saying because they have to maintain the illusion. “Their whole livelihood [is based on] people buying into the lifestyle that they are selling,” he notes. “The instructor can’t turn around and say, ‘It’s not particularly fulfilling, or I’m actually kind of bored of this.'”

“The industry works on creating this alpha male persona. I think the problem is if you build a person for yourself, and that’s how you interact with people, it’s very difficult to develop genuine human connection,” says O’Connor. “As a result, it’s hard to sustain any relationships.” And perhaps that’s the most depressing part of the game: Even when you win, you lose.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram