Before she created her CSA-nominated documentary, many of Marusya Bociurkiw’s students believed that contemporary feminism began with the #MeToo movement. But as her film outlines, a network of feminist media communities existed long before the hashtag blew up in 2017.

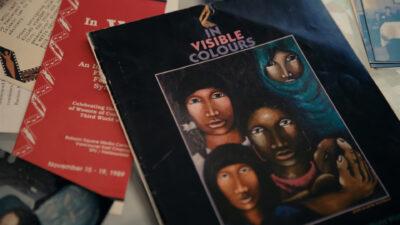

Analogue Revolution: How Feminist Media Changed the World—the first documentary about feminism in Canada in over a decade—spotlights some of the 900+ feminist magazines, newspapers, journals, newsletters, video collectives, film festivals and radio programs that operated in Canada from the late 1960s to mid-1990s.

Bociurkiw, a professor of media theory at Toronto Metropolitan University, was driven to create the film partially because of these shocking gaps in her students’ knowledge—not only around the history of feminist media, but feminism as a whole.

“My students not only knew nothing about feminism, but they found it laughable or scary,” Bociurkiw says. “Younger women students didn’t have tools or a template with which to fight oppressive conditions within and outside of the university.”

Some of the iconic Canadian feminists featured in Analogue Revolution—like Judy Rebick, Sylvia Hamilton, and Susan G. Cole—have been fighting against sexism in the media industry for decades.

The documentary traces all the way back to The Birth Control Handbook, an informative resource about contraceptive options, abortion, and sexuality that was illegal at the time of publication in 1968. Regardless, Montreal Health Press, the group of women behind the handbook, were determined to share this vital information. By 1970, they managed to sell 2 million copies.

Through interviews and deep dives into personal archives, Bociurkiw connects with women across the country who were fighting to have their voices heard, whether it was through indie print publications, Studio D—The National Film Board of Canada’s feminist film studio, or projects like Dykes on Mykes, the longest-running Anglophone lesbian radio show in Montreal.

But not everyone was welcome in this era of feminist media. While BIPOC-led groups did exist, opportunities were far from equal. Bociurkiw points out that Our Lives, the first Black women’s newspaper in Canada, only ever published 6 issues. Meanwhile, the feminist newspaper Broadside, run almost entirely by white women, published 100 issues. “That math was really interesting and said a lot about unequal access to resources,” says Bociurkiw. “We created all-white organizations and didn’t even reflect upon it.”

Many of the organizations spotlighted in Analogue Revolution gained momentum in the 1970s, against the backdrop of second-wave feminism. But as the doc examines, by the 90s, massive cutbacks led to the shutdown of many women and queer-led organizations. Censorship and moral panics fuelled by right-wing organizations were forcing women back into silence.

“It was our first really concerted right-wing, neoliberal federal government and the suffering that was caused, the censorship that came out of that, the organizations that got eliminated—all of that was huge,” Bociurkiw says, warning that it’s all too easy for history to repeat itself. “These things happen again and again in history, but people resist, women resist,” she says. “We have a lot to learn from that history that we can use today.”

By the mid-90s, the momentum may have slowed, but the feminist media movement was far from over. “Feminism never stopped,” Bociurkiw says. “Even if their organizations closed or were defunded, women went to other organizations and brought their feminism there.”

The seeds for the next revolution in the feminist movement were planted: the Me Too era. Social media was a game-changer, allowing individual women to tell their stories instantly and connect with other survivors around the world like never before. But in her film, Bociurkiw was sure to acknowledge the feminist activists who laid the foundation for this groundbreaking era. “I wanted to show how important [MeToo] was but also show its roots in decades of feminist organizing,” Bociurkiw says. “Older feminist activists are like, ‘This is stuff we’ve been talking about for decades!’”

Beyond Me Too, feminist media in Canada is alive and well today. The doc shares how organizations like Didihood and Black Women Film! are thriving, and even embracing the analogue spirit of their predecessors with a focus on in-person organizing and events. For Bociurkiw, feminism means not only looking back, but making changes that uplift women in the industry right now—starting on her own set.

“As much as we could, we hired mostly female crew. We had shorter production days, we had good food. We encouraged the key crew to mentor the younger women production assistants and we created an atmosphere where there could be conversation and questions,” Bociurkiw says.

We’ve come a long way. It’s strange to think that not too long ago, it was unusual to see women behind the camera, on the mic, or reporting a story—that women had to fight for access to equipment and convince male editors that women’s stories mattered. Analogue Revolution paints a picture of an explosive yet imperfect era for feminist media in Canada, a history that deserves to be captured, studied, and remembered. It’s a tribute to the women who paved the way for publications like ours to exist today. And for younger generations of women in media, it issues a call to keep fighting for fair treatment, and to never let our voices be silenced.

Analogue Revolution: How Feminist Media Changed the World is nominated for Best Feature Length Documentary at the 2025 Canadian Screen Awards. The film will screen on May 30 at Paradise Theatre and June 17 at TIFF Lightbox.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram