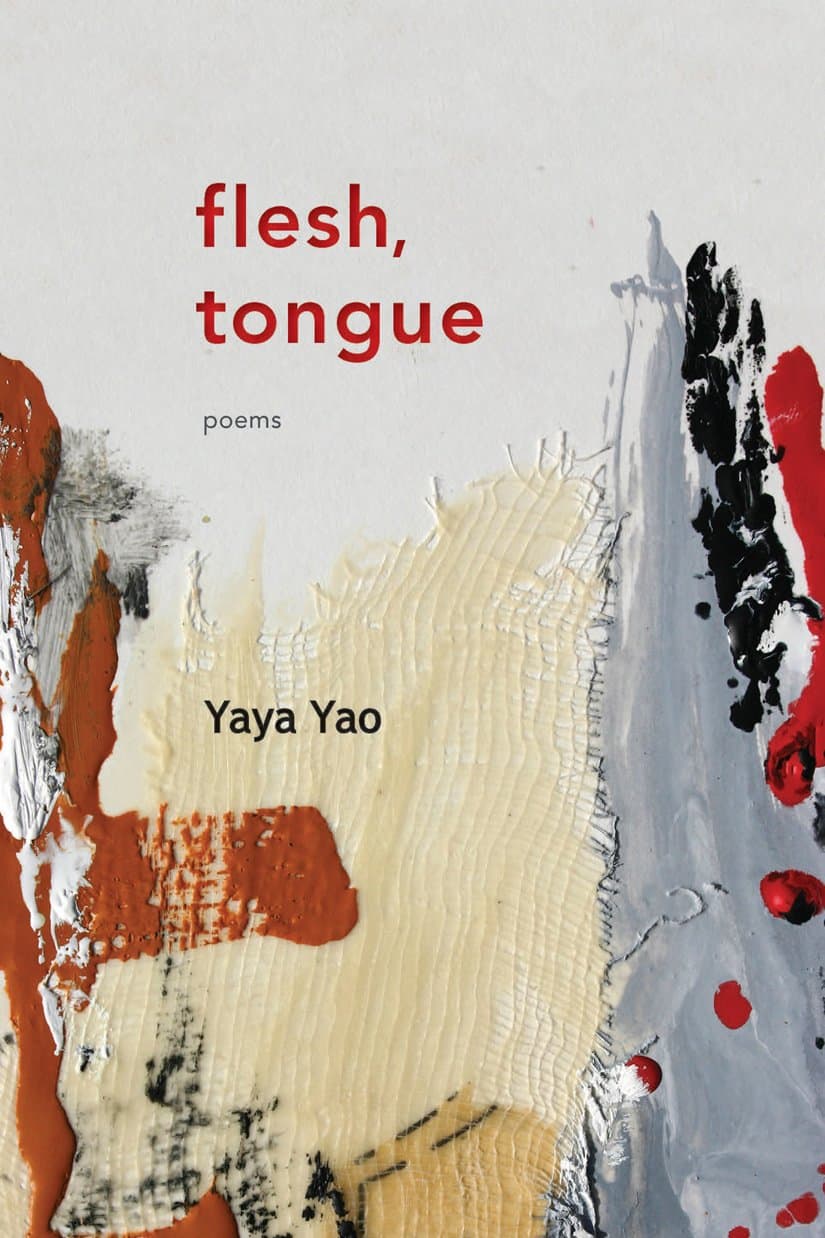

Yaya Yao is an exciting new voice on the Canadian poetry scene whose first collection of poetry, Flesh, Tongue, “confronts her inherited fragmented self and her hunger for a home, using scraps of personal and communal memory to bridge languages, worldviews, and physical distance from her ancestral homeland.” We caught up with Yaya Yao last week.

SDTC: Can you tell us about yourself?

YY: I was born and raised in Toronto’s Little Portugal, where I went to French Immersion and cursed after-school and weekend Chinese class. I live in Sapporo, Japan, with my partner and son, who’s two and a half, and I teach middle school.

What was it like growing up, for you?

I am Canadian by birth, and but I assumed to be from somewhere else because of how I look. I continue to struggle with identifying as Canadian because of Canada’s imperial roots and because of the general assumption that I’m not.

What I’ve come to understand so far is that the place I feel most a product of and the place I most represent is the west side of downtown Toronto, especially Little Portugal/Chinatown. It’s only cliche because it’s true; if you are not of First Nations, Metis, or Inuit heritage, you are an immigrant to Canada. Most of us, especially in Toronto, have immigrant roots. Some of us are simply made more aware of these roots than others. This is about power rather than about having parents, grandparents, or ancestors who come from somewhere else.

Can you walk us through your process to writing poetry?

This is far less consistent and disciplined as I’d like, so I’ll refrain from answering until I’ve developed habits that would generally be considered professional and writerly. I’d love it if someone gave me a deadline on this! Seriously.

Can you explain the structure of the poem Flesh, Tongue?

I was playing with line breaks. Margaret Christakos was a mentor during my first round with Diaspora Dialogues, and she gave me inspiration on experimenting and just taking a playful attitude with the language itself.

There are many ‘language lessons’ woven through your book. Was there a time when you threw yourself into learning other languages?

I grew up with a lot of languages; Mandarin in my immediate family, Cantonese with family friends, Hokkien on my mom’s side of the family, Shanghainese on my dad’s side of the family, and English and French (I was in French immersion) at school. I grew up in Little Portugal, but never learned Portuguese or Italian.

Now, what do I actually speak? Very broken Mandarin. My Cantonese is conversational – I lived in Hong Kong for three years, partly because I wanted to learn the language. That, you could say, was a time I threw myself into an environment because of the language, as an entry point into some kind of sense of belonging. My French is also conversational, but my reading is much better than my oral language, as is so often the case with languages you study in school.

You play with a lot with language, flitting from one to the other. Is there a phrase or word that you love the most (in any language)? What is it, and why?

I love this question. It’s probably “cheen sai,” which I reference in the second poem in the book, “Cantonese Lesson 2.” It’s Cantonese for “past life,” as in, previous incarnation. It’s shorthand for “I must have done something in my past life to deserve this.” I love this phrase because of its attitude and its economy. There are so many ways to cut someone down in Cantonese, all with this muscular, staccato elegance.

You describe people in relation to others a lot in this book (sister’s daughter’s daughter, etc). Is this inter-relational aspect of family (and the ties that bind) missing from individualistic Western culture, in your opinion?

Interesting question. I think this alienation is symptomatic of a kind of spiritual vacuum created by modern capitalism. This is certainly rooted in Western thought, but it’s like global wildfire. It’s everywhere more and more, this disconnection.

Who/what is your inspiration?

My inspiration is, secondarily, everything I’ve ever read, the people and places I come from, and the people and places that I want to say something to.

Mainly I write to reconcile my lack of understanding, and maybe to fight dissociation. I’m trying to make sense of this world, because I really don’t understand it. War, poverty. All violence. I read or I write, I connect to a moment; it’s some kind of start. Poems are amazing because there’s this economy in parallel with the potential to slow time. To let a moment resonate into something deeper, to give it room with your attention.

You dedicate the book to your father, who ‘said he never got my poems’. What does he make of your poetry now?

I remember reading one of my poems to my father, who was unconditionally supportive of me, when I was in high school. He smiled and said with his usual diplomacy, “I guess I just don’t understand poetry.” That wasn’t true. He enjoyed a lot of Chinese poetry, but I think poetry is probably the most difficult genre to crack as a “second” or additional language learner. Or maybe it was my poetry in particular. Of course I’d rather blame it on his “deficiencies” than mine! My father died eight years ago, so the dedication is a way to remember him and celebrate what he taught me. Despite the fact that he “didn’t get”the poems, his teachings are a great inspiration to me in every way.

What do you want people to take away from your poetry?

This is another great question I don’t have an answer to. I always hope that people find something that echoes in them. I hope that there is some kind of pride and even some kind of joy. Mostly I’m curious about what will come through.

Visit Yaya Yao’s website here. You can buy her book, Flesh, Tongue here.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram