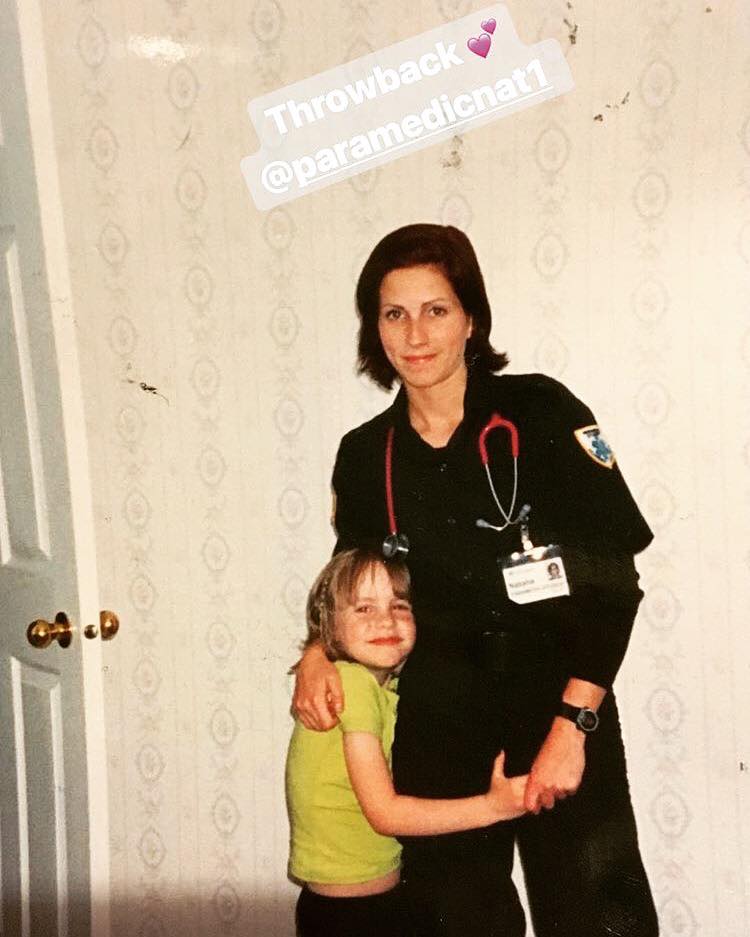

A former paramedic, Natalie Harris is now a writer, blogger and speaker. As the founder of Wings of Change Peer Support, she aims to help fellow first responders in coping with traumatic events. For many Canadian paramedics, depression, addictions and PTSD are common, and their rate of suicide is five times the national average.

Harris says, “A lot of my writing is mental health advocacy based as I battle with PTSD, depression, anxiety and addictions (I have been clean and sober for some time now).”

She has travelled across the country sharing her recovery story through her book, Save-My-Life School: A First Responder’s Mental Health Journey. She will be appearing in the documentary After the Sirens, which looks at the ramifications of being an emergency paramedic (airing on CBC POV Sunday, April 8th).

SDTC: What made you want to become a paramedic?

NH: I wanted to become a paramedic after my mom had a ruptured brain aneurysm when I was twenty-one. She had frequent and complicated seizures that forced me to call 9-1-1 often. My brother would hide behind the couch when my mom had a seizure. The paramedics who got to know us would check on my brother when they had finished caring for my mom. That level of kindness and compassion immediately drew me to the world of paramedicine.

Walk us through an average day in your life as a paramedic.

The alarm clock would go off waaay too early for me—usually around 4 a.m. (I’m not a morning person). I would have a shower, make my beloved coffee and then make the often cold, dark drive to the station.

Once I arrived at work I’d check the ambulance and my bags to make sure they were stocked and ready for a call. We (my partner and I) never really knew when a call would come in, so until it did we’d catch up on life and do things like base duties and paperwork. When a call came in, the tones (speaker) would sound (loudly) and then a voice (the 9-1-1 dispatcher) would announce the call location and a brief description of what the call was. We would head to the truck (we took turns driving and attending) and get the full call details over the radio.

My partner was from the town we worked in and often knew the address locations, so he would head in that direction while I confirmed it in the GPS. Then we would do the call. It could really be ANYTHING—a car crash with trapped patients, delivering a baby, saving someone’s life after a heart attack or helping an elderly patient back to bed.

After transporting the patient to the hospital, we would do the paperwork and most likely get another coffee. We continued this routine for twelve hours and then clean the truck, restock equipment and head home for the night.

At home I would catch up with my kids and make dinner. Then it was time for bed, as the dreaded alarm clock would be making its horrible morning noise only too soon.

The most challenging aspect of being a paramedic for me is dealing with calls that challenge my morals. For example, I was a paramedic at a double murder call in 2012, where the murderer was my patient. After that call I battled with how a human being could harm another human being so badly. I developed what is called a moral injury. Managing the emotions after a call with a child is also very difficult.

The most rewarding aspect of my career is making a difference in people’s lives every day. That difference ranges from saving their life to simply holding their hand—both equally as important, in my eyes. I have also been present for the birth of two healthy babies, which is pretty amazing!

How do you cope with witnessing traumatic events on the job?

I am not on the road as a paramedic anymore because I didn’t cope with the traumatic events I witnessed. I stifled the emotions rather than processing them.

That is why I now advocate for peer support for other paramedics and have founded a peer support group called Wings of Change, which encourages solution-based discussion and education about emotions caused by traumatic events. We don’t discuss the traumatic event details in these meetings—we leave those discussions for the professionals who are trained in trauma care. We have almost twenty chapters across Canada. People can find the meeting locations and times here, under the events tab.

What do you wish more people knew about what it’s like to be a paramedic? What do you hope comes of this documentary?

I wish more people realized paramedics are human just like the patients they care for. Some people call us heroes, and that is very kind, but under our uniforms we are the same as everyone else when it comes to feeling emotions.

We need to make sure paramedics across Canada have the psychological care they require. Some provinces still don’t have presumptive legislation, making getting insurance coverage for PTSD almost impossible. Paramedic lives and families are being destroyed because they can’t take the memories they battle any longer, and rather than focus their time and energy on getting well, they are having to prove over and over again that their PTSD is caused by their work environment, and they are not able to pay their bills while they are doing so.

There is a federal PTSD bill (C-211) waiting to move through Canadian Senate that will help ensure paramedics and other first responders from coast to coast get the care they need. We need as many voices as possible to move this bill along. People can write and tweet to the Senate here and @SenateCA, respectively.

Any advice to other young women who may be considering this as a career?

My advice to future paramedics is to start talking about your emotions from calls right away. Give yourself permission to process the traumatic events you will witness by seeing a psychologist on a regular basis and by participating in peer support meetings such as Wings of Change. Paramedicine is one of the best career fields in the world, and by talking about your feelings early on, you will combat the stigma of mental illness and hopefully prolong your career.

After the Sirens airs Sunday, April 8, 2018 | 9:00 p.m. EST (9:30 p.m. NT) on CBC DOCS POV. The documentary also airs online on Friday, April 6 at 5:00 p.m. EST.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram