The stereotypical depiction of a woman writing love letters to a man in prison is not a pretty one: she is either delusional—thinking she can reform him—or a twisted groupie, getting a thrill out of flirting with a dangerous man.

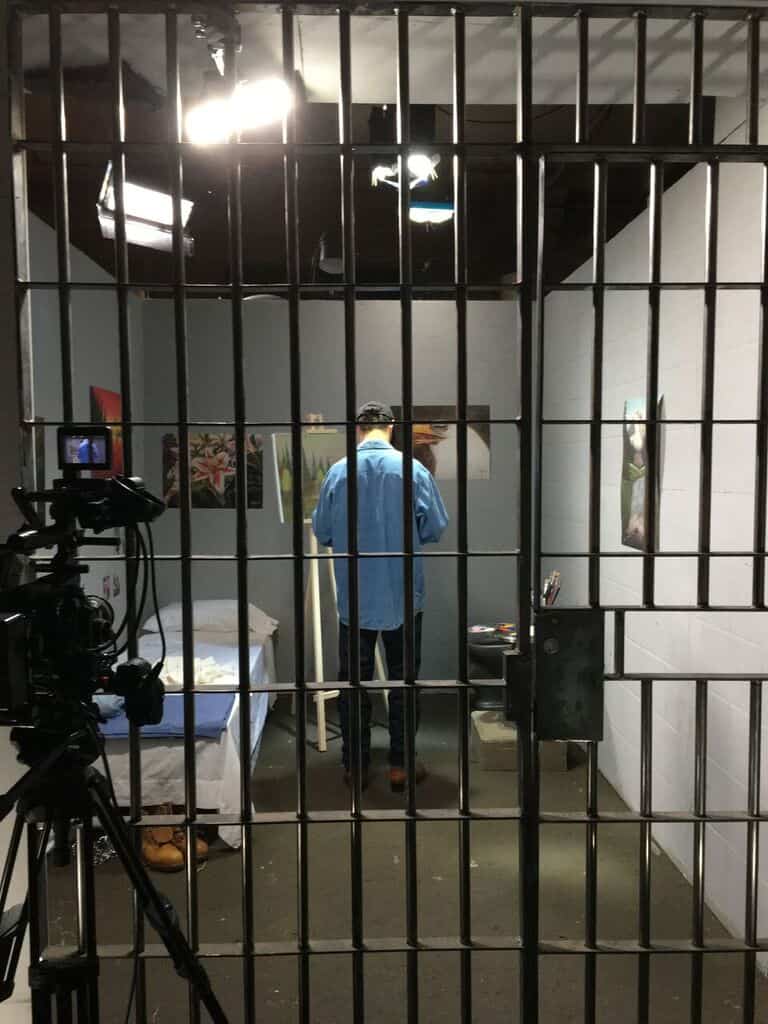

What kind of woman seeks out love with a violent criminal? What kind of woman looks to prison pen pal websites to find a boyfriend? Met While Incarcerated looks at three successful, intelligent and professional women—Brenda, Angela and Journey—to find out why they sought to marry men who are behind bars. The film follows along as they forge relationships with men who are imprisoned for violent crimes, revealing that in many ways, love is harder on the outside.

We chatted with director Catherine Legge this week.

SDTC: What drew you to these three women in particular?

CL: They went against the stereotype. Educated, from nice families, with two married parents. They went to college, they had opportunities in life, they travelled. These women are not just crazy women who are damaged goods and can’t get anyone better—all of those stereotypes. They’re not writing to Paul Bernardo; they’re just like anybody you would meet. I wanted someone that the average person watching could relate to.

Brenda seemed to be the anomaly in the film in that she knew her partner before he was incarcerated. Did you get a sense that Angela and Journey viewed these men as a project? What do you think they got out of the relationship?

They got out of the relationship the same thing anybody does. You wonder why they cross over to the point of writing to someone who is in prison—why would you do that in the first place? Most women who do that are coming from a place of empathy. A lot of them are Christians; they are teachers and nurses and social workers. They have a sense of empathy and think that this would be something nice to do. And then it becomes something more.

The prison environment is sort of an ideal place for infatuation to prosper as the inmate has little else to do than pour his time and promises into his partner, while at the same time, she always knows where he is. Do you think this is part of the appeal of this type of relationship for women?

Surprisingly, most of the men in U.S. prisons work a full day. Every day. Then they have programs or activities, so they’re actually really busy. They’re much busier than we think they are, unless they’re in isolation for some reason. Especially the men I was involved with, because they were all trying to better themselves.

Also, we’ve forgotten what intense communication is like. When you write with these guys and you talk with them, they’re very thoughtful, they really listen, they’re very good communicators because in many ways, their lives depend on it. Ben told me once, “I have about twenty seconds upon meeting someone to analyze who they are, what they’re about, what they want, and what I need to do.” You get very good at reading people; sometimes for the bad (manipulation), but in other ways it’s for the good. There’s no distractions like, you didn’t mow the lawn, or you didn’t pick up the kids. There’s no average mundane things let alone big distractions to get in the way. They have a lot of communication, and it serves them well.

The men in prison are just as likely to be players as they are out here. It happens a lot, especially with these pen pal sites. Ben told me that there are lots of guys in there who are building a squad, and they have ten or twelve women writing them from all over the world, and they balance that with getting money and pictures from them to pass the time. A lot of prison wives’ worst fear is that they’re not the only one.

In your research, did you find these relationships lasted after the inmate was released?

Homecoming is definitely difficult. A lot of the relationships don’t last, period. It’s really challenging to deal with the system, but also living your life alone when you have a partner. It’s like a long-distance thing in some ways, but you have no control over when you can talk or when you can visit. So many aspects of our lives are used to an immediacy: we can do whatever we want, whenever we want. That’s an adjustment. Longing is a beautiful thing sometimes in a relationship. It’s all you can think about. That is lovely for a while, but reality is a lot harder.

It’s impossible to imagine how ill-prepared the men are to come out in today’s world, especially if they’ve been away for ten years or more. They’re not prepared for what it’s like out here, it’s so different.

There are barriers to success, but one of the biggest things almost nobody talks about is incarceration syndrome, where people become institutionalized. They just become their environment. If you think about soldiers in stressful situations, [their] fight or flight reflex is constantly on alert. For these men, pretty much every interaction in prison has serious consequences. They’re living in this heightened state for years; it’s basically like trauma. When they come out, being in a regular world where people are nice to you, it’s like, “What do you want from me? Why are you looking at me? Why are you talking to me?” It’s unnatural for them.

How did making this film alter your perspective?

Before, I think I felt like everybody else did. Like, “Who are these guys and who would ever write to them?” I work in series television and I was trying to cast a home-renovation show. I typed into Google “Sexy carpenter with a sense of humour,” and a prison pen pals website popped up. I looked at it, and it just drew me into this incredibly funny and scary world. I took pictures and sent them to my friends, like, “Here’s your new boyfriend! Haha!”

I got past that fairly quickly and started to meet people and hear their stories. It changed my point of view completely. I told their love stories as they see them. I used all of my tools available as a filmmaker to make their love feel real for everyone to watch it. I wanted to go the opposite way and say, “They’re not them, they’re us.”

At the same time, they committed violent crimes—against women, in a few cases. What is your responsibility to the victims’ families when it comes to dealing with this subject matter?

I was very cautious about the subjects that I chose. Everybody on our team, to this day, we have very mixed feelings about it. Just like [the inmates’] families do. The point is not to ever gloss over the crimes or pretend these crimes aren’t terrible, because they are.

Doing a story like this in the context of the #MeToo movement was a challenge, because we’re not in a forgiving place right now. I would go from reading something about Weinstein to talking to one of these guys on the phone. These guys aren’t Justice Kavanaugh, who gets accused of sexual assault and is appointed to the highest court in the land. They are caught. They admit their guilt. They live out their lives in prison. Every single day, they wear their guilt. Their entire life is about that. They’ve committed crimes. They’ve paid a price. Whether it’s enough is not up to me to decide. But they really want to change their lives, and they’re working at it every day. What else can we ask?

Do you believe that the prison system works?

It’s interesting because a lot of these guys say that prison changed their lives. Sonny says it at the end when he gets out after thirty-one years and says prison saved [his] life. He went in when he was twenty-two. Ben was in and out most of his life. He was a drug dealer; he was abusive. For many, prison saves them from doing worse, or from death itself. Just being removed from addiction and poverty and violence in your everyday life is a bonus.

But the prison system itself? No, I don’t think it’s serving people. I think in many ways, Canada is worse than the U.S. because we don’t offer people the programs they need to heal from the trauma that most of them have experienced. We hope that after living in a violent world for a number of years they come out better somehow. That makes zero sense.

What do you hope audiences take away from this film?

I hope viewers have moments like I did, where they think about when they were twenty or twenty-one and the people they knew and the things they got away with. Because that’s how close we are to the idea of things going wrong. I thought of old boyfriends and thought, Man, that could have been my boyfriend, easily, from when I was seventeen.

When I talk to these guys, they are real people who had real lives. For one reason or another, they get down a slippery slope that leads to a terrible crime. I hope people watching will come to it from a place of empathy; if people pay the price at it, and really work at it—do everything they can do—why shouldn’t they have love and get to be loved? To be brand new in someone’s eyes? These people are coming out someday into our world. Who do we want them to be? Someone who has love, and a family, and a place to go, and hopes and dreams? Or not?

Watch Met While Incarcerated on Sunday, March 31 at 9:00 p.m. ET & PT on CBC’s documentary channel.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram