by Lizzie

Why we should care: Ever gone to the Bata Shoe Museum and felt queasy from the three inch long shoes worn by Chinese women with bound feet? Well back in the early 1900s Qiu Jin said no to size one shoes, left her aging hubbie, began a journal advocating for Chinese women’s rights and (as a school principal) trained a female army of revolutionaries against Manchu rule. Awesome, all my school principal did was ask me to tuck in my shirt.

For her biopic we’d cast: Jin Jing, the paralympic athlete who became a national hero after defending the Olympic torch from French free Tibet protesters.

Two traits we admire: 1) Secrecy: She helped run clandestine bomb making facilities, trained an underground army, and didn’t reveal her compatriots when tortured by the Imperial Army. I’m pretty sure Qiu Jin wouldn’t spill the beans if you told her about that unfortunate one night stand with the mailroom guy. 2) Lyricism: She didn’t just fight for the right, she fought for the right with poetic flare, describing the removal of her bound feet so: “Freeing my bound feet, I washed away the poison of a thousand years, and, with agitated heart, awakened the souls of all the flowers.”

What high school textbooks didn’t say: Um, everything? Female Chinese revolutionaries weren’t really given top priority in the Ontario high school curriculum.

Style best described as: A CK One ad circa 1905. Qiu Jin favoured Western style caps, bow ties and suits because she believed in Western style democracy. She would have blended in well with the sexually ambiguous Oscar Wilde set.

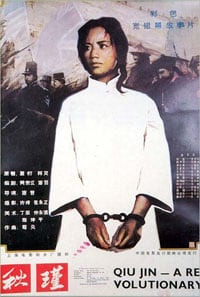

How she’s celebrated: The People’s Republic eats up the leftist heroism of Qiu Jin; stories and statues abound. A museum of her former residence is in Shaoxing and two movies have been released: Qiu Jin A Revolutionary (1983) and Qiu Jin: The Revolutionary Heroine (1953).

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram