On December 6, 1989, fourteen young women died at the École Polytechnique.

They died for having the audacity to want an education. They died because they wanted to be engineers, a profession historically dominated by men. But most of all, they died because a man wanted them to.

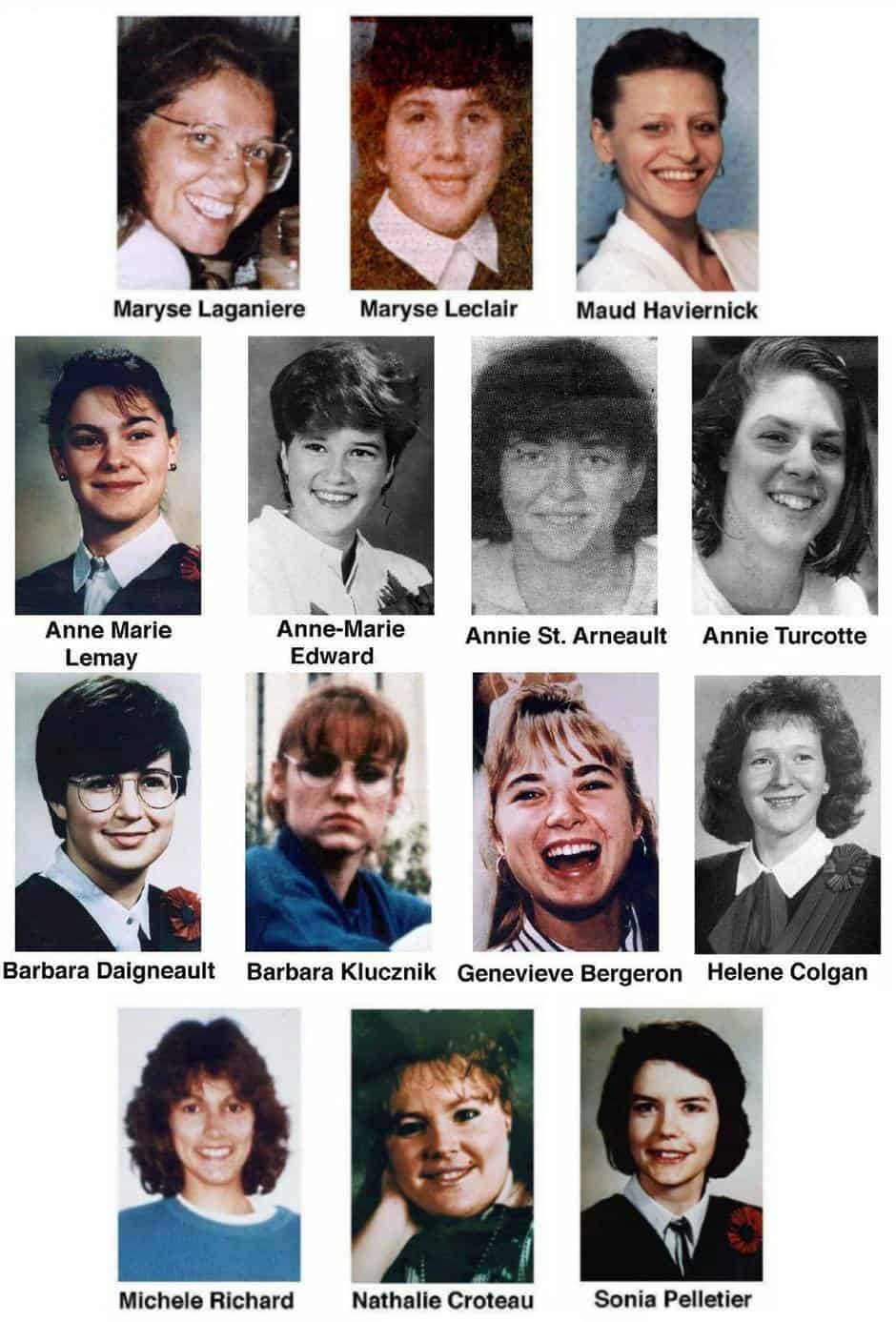

Their names were Geneviève Bergeron, Hélène Colgan, Nathalie Croteau, Barbara Daigneault, Anne-Marie Edward, Maud Haviernick, Barbara Klucznik-Widajewicz, Maryse Laganière, Maryse Leclair, Anne-Marie Lemay, Sonia Pelletier, Michèle Richard, Annie St. Arneault and Annie Turcotte. They were people with dreams, families, friends, good days, bad days, strengths and challenges. We’ll never know what extraordinary – and completely ordinary – things these women might have done. We’ll never know, because Marc Lépine took a gun, entered the Ecole Polytechnique, separated the women from the men, and opened fire. As he did so, Lepine declared, “You’re all a bunch of feminists, and I hate feminists!” This was how he announced his victims’ death sentence. Their crime? Winning entry to engineering school when he could not.

“I hate feminists.”

Those words reverberated through our country. Lépine’s words haunted the families of the women who died, and the families of all women, who knew their daughters could just as easily been singled out for death. Because that is what an act of terrorism is – a symbolic crime designed to scare all members of a group, to let them know, it could have been you.

I often wonder how my own parents must have felt – how terrified all parents of daughters must have felt – when they learned fourteen women were murdered for their ambitions. In December of 1989, my mother had just given birth to her second daughter. Sometimes, I imagine her two months postpartum, holding my little sister in her arms as she heard the news, knowing she’d brought another girl into a world where men wanted to kill her.

As a country, we say we remember. To prove we’ll “never forget,” our politicians declared December 6th the National Day of Remembrance and Action on Violence Against Women. We repeat the names of the young women, whose lives were cut tragically short, wondering who they might be if only we’d been able to protect them. And yet, our country has failed – or forgotten to – give these remarkable women the legacy they deserve; we have not ended violence against women.

As I sit here, thirty years later, the world is still unsafe for women – or anyone who isn’t a cisgender white man. The Montreal Massacre was supposed to be our wakeup call, a rallying cry to save Canada’s daughters. Each year we remember the fourteen women who died at École Polytechnique, we say their names, and little changes. Violence against women and non-binary people lives on…

It’s far too easy to think of examples of gendered violence in the years since the massacre in Montreal. On April 23, 2018, Alek Minassian rented a van to mow down pedestrians on Yonge Street. Similar to Lépine, his act of terrorism was motivated by hatred against women, a hatred born of male entitlement. Lépine was enraged women were taking “his” spots at engineering school, while Minassian was mad women wouldn’t sleep with them. The details are different, but it’s still the age-old story: a man is offended by the idea of women he can’t control, so he kills her.

But it’s not just terrorism against women that persists. Intimate partner violence accounts for a quarter of all calls to the police. Canada’s First Nations women are more than three times as likely to be murdered as non-indigenous women, and those who attack them are punished less for these crimes. As much as we Canada likes to tout itself as an LGBT-friendly country, crimes against transgender and non-binary people are also on the rise.

Some insist it’s only the bad people – the criminals – who beat up on women. With #MeToo’s beginning in 2017, we’ve had more public discussions about gendered violence and harassment, but it doesn’t seem like the right people are listening. When a feminist writes an article calling men out for gendered violence, we hear a self-righteous chorus of “Not all men!” from self-identified “nice guys,” who don’t understand why they can’t ask the 19 year-old intern on a date. They lecture us about a supposed “War on Men,” when other people are actually being killed for their genders. Sometimes we try to debate with these supposedly good men on Twitter, sometimes even in person. But we fear it’s pointless, and it usually is.

The sexists aren’t just middle-class white men on the Internet, they’re in our government, too. In the 2019 election, 45 anti-choice Conservative candidates were elected to parliament, people who would vote to curtail abortion access, people who advocate what author Margaret Atwood refers to as “forced births.” Hating women isn’t the purview of a handful of societal misfits. Now it’s a Canadian political movement.

As I write this article, on the eve of the thirtieth anniversary of The Montreal Massacre, I am pregnant with my own daughter. Like generations of mothers before me, I worry I won’t be able to protect my daughter from a world that hates women. When I recall the events at École Polytechnique, when I consider what Lépine’s victims lost – and the loved ones who lost them – I am overwhelmed. We failed to save these women, but Canada owed it to them to save those women who came after.

Thirty years ago, fourteen women were stolen from us. We promised never to forget them. But the hardest part of remembering is this, knowing how easily it could happen again. We owed the victims of the Montreal Massacre a legacy, a legacy of becoming the catalyst for lasting change; that is a debt our country has not paid. It is a debt that presents in the form of underfunded women’s shelters, the epidemic of sexual assaults on university campuses, and the mortality rates for First Nations women and girls. It is time our country’s leaders to make sure that debt is paid.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram