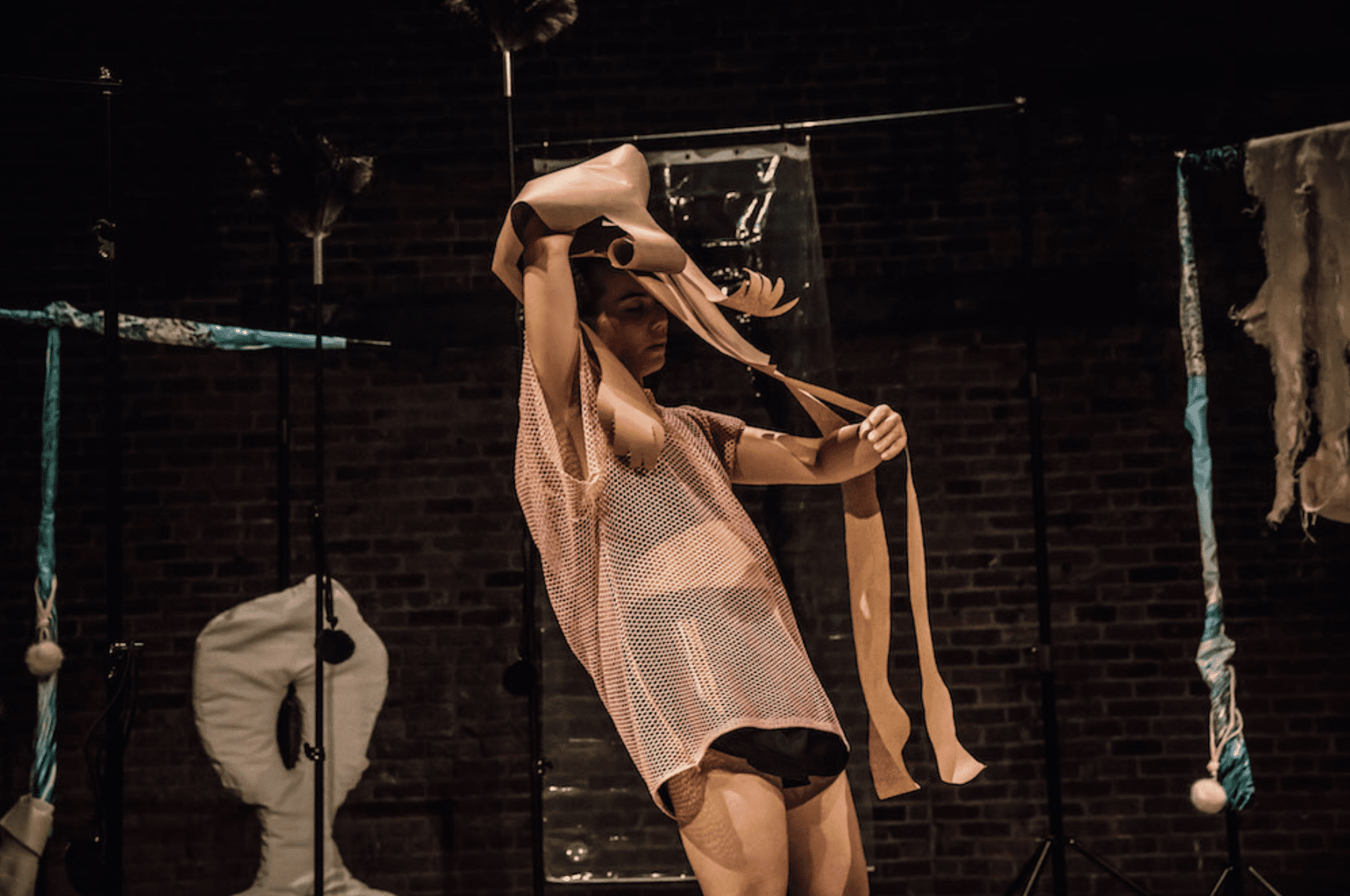

Liz Peterson’s Performance about a woman opens this Thursday as part of RUTAS 2018. The performance incorporates a series of full-bodied masks to explore the idea of identity while asking us, “What could an audience want from a performance about a woman?”

Written and performed by Peterson, the performance is accompanied with an arrangement sung by Polaris Music 2017 Prize winner Lido Pimienta. We asked Peterson about the piece.

SDTC: How did Performance about a woman come together?

LP: This project has been with me since 2014. I wanted to make something that allowed me to embody some complicated views of myself. Also, I channelled some demons. I guess it was like therapy. In a lot of ways it still is. My therapist was actually pretty fascinated by it as a proposal. She came to see the first iteration at the AGO.

I was very inspired at the time by my friend Meg Foley. She’s a choreographer based in Philadelphia, and she has a practice called Action Is Primary. I took her workshop while she was staying with me in Toronto. It rocked my world and inspired me to make something. She’s a very special person. I’ve told her that I owe this show to her.

What is the central idea/theme around this performance?

Every time I come back to this performance, I have a moment of regretting the title. It’s both too broad and awkwardly specific. A European presenter once laughed in my face when he heard the title. In the end, the title is actually the most dynamic thing about this project. This performance has changed with every new iteration, and, until recently, I couldn’t articulate why that was necessary, but now I understand; I could never make a show that was about the concept of being a woman and do the same thing for four years. It’s forced me to confront myself over and over again in a rapidly changing landscape of identity politics and through intense change in my personal life.

The idea at the heart of it is that in order to redefine or step outside of the normative, you actually still have to be in relation to the norm. It’s like trying to write a paper on queer politics without making reference to Freud. You can say that you disagree with him, but you still have to acknowledge his work; otherwise, you’re not taken seriously. So, as impossible as it is, the challenge of this piece was to embody the word/symbol/myth woman and to change it for myself, to try and shake off my own internalized misogyny.

I wanted to explore the ways that my body performed itself. There is so much meaning in the body that I thought maybe my body could lead me to intuitively devise a piece where I could perform myself outside of the construction of woman. This idea led me to develop a practice where I make sustained eye contact with individual spectators. This intimate exchange is repeated throughout the performance, and then I embody what I think they want to happen next. The task is about intimacy, projection and desire.

Since its inception, the work has also led me to embody ancestral figures. I’m mixed race; English, Burmese and Indian. One side of my family are working class Mancunians, and the other side are descendants of English colonizers, Burmese Bamar and unknown Indian lineage. The erasure on that side of family is quite intense. I’m white-presenting, so it’s something that is hard to discuss. I don’t often encounter a context where I can openly talk about my experience, so this has also found its way into the performance.

How has your sense of identity evolved over time?

Since my early twenties, I’ve identified as queer. I was in a heterosexual relationship for a long time though, and that’s not an easy place from which to claim queerness. I felt that as long as I stayed true to those politics, it was possible to be in a hetero relationship that is politically queer. It was very central to my identity, in fact, but that relationship ended earlier this year. My partner was having an affair with a woman who I would describe as very heteronormatively feminine, and that has caused a real reckoning within myself. I realized that my own version of femme was a way of dealing with old wounds that were still there. I thought I had moved on, but I realized those feelings never go away. I had just found a way to quiet them.

What does being a woman mean to you?

The other day someone asked me how I identify. I said I wasn’t sure how to answer that question. Then they said, “What does your sex life involve?” I said, “Currently my sex life is a void, but all bodies are welcome into it.” I refer to myself as a woman almost as a joke; my default as a performer is a maniacal clown that my friend Eroca describes as a sexy troll. I guess that’s what I’m asking for: to seriously consider a sexy troll as also being a woman, or (more simply) to accept the creature within.

What draws you to utilizing masks in performance?

I started using masks in this piece very recently. It’s a new interest of mine. I like working with things that really fail as masks (e.g., craft paper or a scrap of burlap) and animating them. I’m interested in how they perform these very intense characters that I’ve developed. I call them masks, but they are in fact faceless full-body cut-outs. I can’t really describe why, it’s just what I’m doing right now.

What did you especially love about putting this production together?

I love being able to present this as part of RUTAS. My family has lived in Chile for a long time now; it’s the place that I’ve called home the longest of anywhere. It’s another important part of my identity, being a Gringa. Bea Pizano (of Aluna Theatre) has always accepted me as another kind of South American diaspora. I’m so grateful for that.

What do you hope audiences come away with after viewing this piece?

Intimacy is terrifying because it forces us to feel and see ourselves, but ultimately we come to know ourselves through others. I guess I hope there’s a window of opportunity in this piece for the spectator to look into the eyes of a stranger and feel permission to experience that intimacy in the context of a performance.

Performance about a woman runs from October 4 to 7 at Ada Slaight Hall. Grab tickets here.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram