When I was younger, I had nightmares about food I’d hidden, piles of candy and cakes hoarded away. My subconscious would bubble over with hot shame, and in my dream, I’d frantically try to keep the stash a secret from other people. When I was alone with the food, I discovered it tasted like poison—tinny, as if all the sweetness was drained out.

I saw my first nutritionist when I was 10 years old. She told me to keep a diary of everything I ate, and gave me herbal supplements for weight loss. Since then, I’ve struggled with disordered eating. Food has been many things to me: a lifelong companion, a comfort, a crutch, a bad boyfriend, a welcome escape. Our bond is a tangled and complicated one, built on the extremes of “too much” and “never enough”.

When the pandemic hit in 2020, I started watching The Great Canadian Baking Show with my mom. It became a safe haven for me, and a bonding experience for the two of us. It was freeing, watching the artistry and the failures and the triumphs and the emotions—all unapologetically wrapped up in food.

Many of the narratives around food that I grew up with were far less joyful, and made me feel like my appetite was unruly and needed to be carefully regulated. Desire for food would lead to gluttony, which would lead to weight gain, which would lead to failure. But the more I tried to curb my obsession with food, the more I was consumed by it.

This led to a growing distrust of my mind and my body. I found myself relating to characters like Templeton the Rat from Charlotte’s Web, instead of Fern Arable, the young heroine who was roughly my age. Templeton would scrounge around, joyfully consuming his nighttime smorgasbord, his stomach expanding into hugeness. Something about his character reached in and touched me, made me feel fully exposed and perceived.

I’m the rat, I thought to myself. Not the sweet girl, not the brilliant spider, not the runty, innocent pig. I’m the rat. The rat who eats garbage.

I continued to relate to food in this way, and existed in this dichotomy of scarcity and abundance, for many years. The stories I was shown both onscreen and off reified the belief that “bad” foods were to be avoided if I wanted to be a normal, happy girl.

There was an anti-fast food poster in one of my teacher’s classrooms in high school. It featured the backside of a very large man in a swimsuit, the coded messages being: “you are what you eat” and “there’s nothing worse than being fat.”

This same teacher was confused when we went on a class trip for a week and I ate close to nothing, as if there couldn’t possibly be a correlation between the inherited attitudes shown in the poster, and my desire to be thin at any cost. This was the culture many of us grew up in, the culture we still live in, where desire is feared, where an unchecked appetite is seen as shameful.

Having these ideas instilled in me through my formative years made it easy for me to fall into “wellness” traps as I entered my twenties. I’d jump from diet to diet and/or heavily restrict my intake. On one occasion, I only drank a concoction of lemon juice, cayenne pepper and maple syrup six times a day, for two weeks straight. The deprivation, the act of abstaining, was itself intoxicating. I told myself (with some help from celebrity testimonials) that my body was being cleansed, that it was being made pure from the toxins that plagued it.

None of this is sustainable or healthy, but it is sadly common. It may “work” in the short term, but it catches up with you. Eventually I had to come to terms with my relationship with food and the stories I was being told, including the ones I was telling myself.

In addition to seeking help through therapy and medication, I became more intentional with what surrounded me, curating my social media feeds to introduce myself to different bodies and mindsets, like Health At Every Size (HAES) dieticians, and activists like Sonya Renee Taylor and Aubrey Gordon.

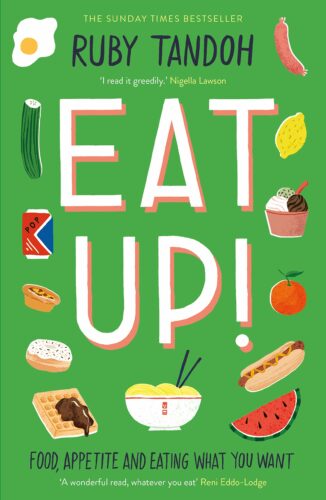

In 2018, I read The Great British Bake-off alumna Ruby Tandoh’s book Eat Up: Food, Appetite and Eating What You Want. In her book, Tandoh talks about food as something to be enjoyed and celebrated, just for the sake of it, without any guilt. She talks about history, community, culture—all the wonderful elements of sharing food. She talks about nutrition as just one aspect to be considered, that the joy in food is “intimately connected” to our mental and physical health.

A lot of these ideas were familiar to me, but putting them in place in my life felt truly radical, and helped me on my journey to healing.

In an episode of the fourth season of The Great Canadian Baking Show, one of the contestants, Dominike, shares with the judges her previous struggles with disordered eating. “I was afraid of food,” she says as she works on her babka, the bake that helped her heal. Judge Kyla Kennaley affirms this feeling of returning to wholeness through creating in the kitchen. “This is what baking is all about, it’s about bringing people back to themselves and back together,” she says.

After a lifetime of narratives that encouraged my unhealthy behaviours, The Great Canadian Baking Show feels like a celebration, a reminder that food is more than sustenance. Food is more than macros and calories and discipline. And even though there are people who don’t or can’t see this, I can remind myself that I am not them. They are not me. I have autonomy.

I’ve been inspired not only in my recovery, but in my work. As a portrait photographer, my job is typically to make people look like the “best” version of themselves. This almost always correlates with Western standards of beauty and thinness. I feel complicit in this. I know it perpetuates harmful ideals, and it has taken its toll on my own body image. The ubiquitous use of retouching software, and the pressure on people, particularly women, to look perfect, all play a role in this.

But throughout the first year of the pandemic, as I watched all episodes of the Baking Show, I was drawn back into the kitchen. I made blueberry cake with lemon drizzle, chocolate fudge with sea salt on top, cinnamon sugar donuts, a lemon tart with pretzel crust, maple honeycomb ice cream from scratch. And I would photograph my bakes, which ignited an interest in food photography.

When I make something and capture it, I am recognizing the beauty in preparing food for myself and for others — in the sharing, in the gratitude, in the happiness. These are simple, normal, basic things. But to me, they feel hugely significant.

This fairly new fascination with baking and food photography is not without its complications. My old food rules are still present, and it’s an ongoing struggle. But I’ve been able to challenge these ideas, and invite new ones to the table. I’ve been able to bring a bit of myself back from the shadows.

There was a time when I wouldn’t allow myself to eat a whole banana, let alone bake a cake and eat a piece without incident. There was a time when that would throw me completely off kilter. I wouldn’t be able to see myself. I couldn’t identify myself or my purpose without rigorous constraints around what I ate.

But when I surround myself with different stories, stories of joy and messiness and human vulnerability, my brain starts to shift. The old narratives don’t go away entirely, but new ones eclipse them. I find joy and peace in these narratives.

Even if I’m never fully healed, I’ve begun to see myself wholly. When I look in the mirror, I understand that I am both fallible and worthy. It is okay to feel a lot, and to need a lot. To be passionate and impulsive and indulgent. It is okay to know what I want my story to be, to know what I want from life, and to dig in without shame.

JK Murphy is a writer and photographer from Halifax, Nova Scotia who is passionate about mental health and body politics. She loves the ocean and making people laugh. She has a degree in Journalism from the University of King’s College. You can follow her on Twitter @wordsfromjenn and Instagram @jk.murphy.

This essay was selected as part of Shedoesthecity’s New Voices Fund, established to help continue offering opportunities to talented emerging writers with less than 20 bylines. More info here.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram