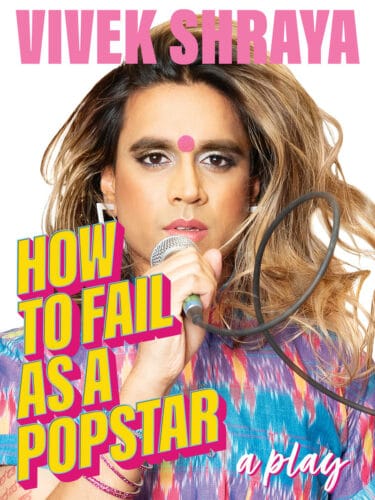

Vivek Shraya is many things. She’s an artist whose body of work has crossed boundaries in music, literature, visual art, theatre, and film. Her books have been described as “cultural rocket fuel”, and her music has been nominated for the Polaris Music Prize. She is an assistant professor, one half of the Musical Duo Too Attached, and the founder of the publishing imprint VS Books. She’s the author of several books, including The Subtweet, I Am Afraid of Men, and God Loves Hair. She’s also a failed popstar, a journey she talks about in her latest book, How to Fail As a Popstar, based on the 2020 play by the same name.

—

Failure is kind of embarrassing to talk about, or even think about. It’s so often framed as a story of resilience, or growth, or as a stumbling block that happened on the road to success, but we never really talk about what happens when we just… fail.

I was very grateful to have a chance to chat with Vivek Shraya about her latest book How To Fail As A Popstar– not just because I’m a huge fangirl (I am!) – but because over the last year, the pandemic has changed my life (and the lives of many others) in so many ways. So many of us have had to deal with things not working out the way we wanted them to, and we’ve also had to learn to cope (or not cope) with hard feelings.

Our conversation was inspiring – but not in the way stories about failure usually are. Don’t call it a comeback – [she’s] been here for years. Vivek still isn’t a popstar – and has accepted that it’s probably never going to happen. However, chatting with her was refreshing and illuminating in so many other ways. Vivek was firm in her belief that stories of failure don’t have to be generative, or about how resilient the person is. She was honest about her failure, and her humiliation in talking about it – but also honest about how liberating and healing it was to name failure. She spoke about so-called “negative” feelings, how hard they can be, and how important it is to feel them anyway. Her words were a tonic – to the endless pressures we face (from every angle) to succeed, and hustle, and excel, and be perfect.

I was grateful for the chance to sit down with Vivek Shraya and talk about failure, and why it’s important to honour it, and to mourn your dreams.

—

Ameema: How to Fail As A Popstar is your third book that was released during the pandemic. What has it been like to have not just one, but three huge accomplishments occur, and not be able to celebrate them in the ways that you used to?

Vivek Shraya: It’s challenging. When The Subtweet came out, almost a year ago now, I really tried to embrace it, thinking “it’s a book about the internet, so we could just promote it on the internet!”. But now, with How to Fail As A Popstar, it’s hard not to feel… disappointed. It feels anticlimactic. Like books that have been coming out in the last year, just kind of disappeared into the void. You don’t get the kind of longevity or longer visibility that you’d get with something like a book tour. It’s a bit disappointing, but I feel fortunate to be able to put out art in any capacity during this time.

I think Popstar, for me, has a particular heaviness, because it’s tied to the play, which came out last year. The 12-day run ended on March 1st, and it was such a high. We had all these plans about taking the play nationally, or internationally, but of course, those things didn’t happen. I do feel lucky that there’s a book version to honour the work, but there’s definitely something about live events – whether it’s live book events, or live theatre, or performance, that I think that got lost [over the last year].

A: So… You wrote a book about failing…why was it so important for you to focus on your failures?

VS: I think that culturally we LOVE to celebrate success. We love success stories – we want to hear about how people are reaching their goals, and we want to be inspired by each other, and by success…But for every success story there are thousands of stories of failure, and to pretend that those don’t exist can be painful. But I am of the mind that [when it comes to] any difficult emotion, the only way to really process it is actually to engage with it, and honour it. Whether that includes depression, or – as I mention in the book – feelings of jealousy, all of these, so called “negative” feelings and emotions, including failure, need to be witnessed before you can actually move forward.

A: I really love that, because failure – like money, or embarrassing health issues – isn’t something that’s typically spoken about in “polite company”… So much of your previous work has been vulnerable, but speaking about your failure so publicly must be rooted so deeply in vulnerability and shame… How does it feel to have a story of your failure out there in the world?

VS: It’s interesting because most people’s response – even just to the title – is to reassure me, like “No, you’re so successful! You’ve done this, and that”. I think this comes from a really well-intentioned place, but it speaks to the fact that we don’t know how to create room for people mourning their failure.

I will say that there was something about the play, about getting up in front of 100, 200 people to say I failed at something which was actually kind of humiliating. Because, again, this isn’t something we do. We don’t stand up in front of people and say “I failed.” But, humiliation was a kind of freedom.

A: Brendan Healy’s foreword references this idea of needing to have “funerals” for your dreams. Can you talk a little bit more about that?

VS: With any project, I really like to challenge myself, and do things that make me deeply uncomfortable. One of the things that makes me really uncomfortable about theatre is audience participation, and while we were workshopping this play, I had a desire to do this to other people [both laugh]. I was really curious about including some sort of interactive component to the play, because the subtext of the play is trying to create space for others to honour their failure too.

One of the ideas we talked about was creating some sort of live shrine or altar: A failure altar, if you will. Somewhere that people could light a candle for their failures, or write a note about them. I think that’s where Brendon got this idea about funerals from. Based on conversations about taking a moment to honour our failures through ritual.

Photo by Dhalia Katz

A: That’s so powerful, and honestly, the ostentatious part of me is really into the idea in its literal form. Like, if you were to have a funeral for your failure as a popstar, what would that look like? Was that your play?

VS: That’s a good question. I do feel that in a lot of ways, the play is the funeral. Every night that I performed, it did feel like a ritual to honour this dream. Being able to continue exploring this story as a book – each iteration has allowed me to… “Keep the failure alive”, so to speak, and there’s something about that that feels… healing.

A: In ‘How to Fail As A Popstar’, you reference 40 reasons why you failed. How important was it for you to have an answer to the question: “Why did I Fail”? Did having a reason (Or 40) help you accept it?

*VS: While we were still workshopping the play, my director told me to make a list of why I might have failed. After writing the list, it suddenly felt like a key part of that play. It’s called How to fail as a Popstar, but in some ways the play really is grappling with why I failed as a Popstar.

That was kind of the central question: “What did I do wrong?”

I performed in malls in Edmonton, I worked with the right producer, I spent a lot of money on my first album, I moved to Toronto, and showcased at Canadian Music Week... It feels like I did a lot of the things that many artists have done to be successful… Why didn’t it work for me? What was missing?

I think that list was an opportunity to not only think about those reasons, but also engage with some of the things that are outside of my control, like homophobia. I think the hardest thing about failure is in the things that you can’t change yourself.

A: How do you decide that you have failed?

VS: Popstardom is very much tied to youth. I mean, I’m sure you’ve seen those memes that say “Don’t worry… Toni Morrison didn’t write her first book until she was 40”, but nobody says “Don’t worry… Genie in a Bottle Came out when Christina Aguilera was 55“, right? This isn’t to say that I can’t have a healthy career as an Indie musician, but pop stardom is very much tied to age.

Photo by Dhalia Katz

A: Should your terms of success (what you consider as you to be successful) be nonnegotiable? Is settling also a form of failure?

VS: I can’t speak for everyone, but I think part of the problem was that in my thirties I pretended like my dreams were negotiable. By trying to be okay with the success I had elsewhere, I was trying to be okay with not being a popstar. Although I’m really honoured, and grateful to get to be a writer, and to make art that people engage with, I think I need to be honest with myself that none of this was the stuff that I wanted. So, for me, personally, it felt really important to not negotiate that.

The second part is a bit harder. I can’t say that I settled. If anything, I’ve been more active in the years following. I think everyone has to negotiate their dreams in different ways, and I think settling, for some people, is a form of survival. I know people who, as soon as they turned thirty, they weren’t successful with their music dream, so they went back to school, or changed careers. I think you can look at that and say they just settled, but I think there’s a reason why people give up, or change the course, and I think everyone has to do what’s right for them.

A: In this book you reference your musical nemesis —Justin Timberlake, and in your 2020 novel, The Subtweet, you explored the complicated nature of personal and professional jealousy — especially in between marginalized people… how do competition and jealousy shape [our] perceptions of success and failure?

VS: I think the biggest thing is that we never really know what’s happening on the inside. I mean, there are artists I’ve looked up to, or who I felt competitive with, or jealous of, for whatever success they are having, but it’s only in conversation with them that I realize that they aren’t necessarily where they want to be, or the success they’re having isn’t the success they want. On some level, I think most artists do probably feel unsuccessful in one way or another, so I do think for me it’s been useful for me to remember that what I see on social media, and no matter how successful someone might be, you don’t know what’s going on for them on the inside.

A: Are there other famous examples of failure that inspired you, or helped you grow? Or helped accept your own failures?

VS: Failure stories are always tied to the ways the individual was resilient, as opposed to “this person failed. It was terrible.” [both laugh]. You know, I can’t think of a story of failure that inspired me to tell my own. I think, if anything, it’s the ways in which stories of failure are always repurposed into stories of resilience. It was all these stories of resilience actually that helped me shape what kind of story I did NOT want to tell [laughs]. Sometimes, it’s less about how something inspires you to do the thing, and more about how something inspires you NOT to do that thing. [laughs].

Photo by Dhalia Katz

A: What do you think society would look like if we were just open about failures, and didn’t frame them in this generative way, and just acknowledged that sometimes things fail. Do you think there’s a reason we don’t do that now?

VS: It’s such a painful thing, and I understand why people don’t want to do it. I understand why failure is not something people want to grapple with. Because the way that we survive is by being resilient. And I guess that’s the truth. If I just let myself… bathe in my failure… I probably wouldn’t get up in the morning!

One of the reasons why I was able to write this play when I did – at 38, rather than when I was 29, and my record deal was faltering and it was really looking like the end was that since then, I’ve acquired success elsewhere. And since then, I’ve had that to bolster me. Accepting your failure – especially publicly – isn’t a path for everyone, but I think, going back to the idea of funerals for your failures, it would be so wonderful if we could do it even privately. Like, in conversations with friends, where they’re saying “no, no, you didn’t fail”, you can push back, and say “Actually, I really feel like I failed at something.” – and to really have that be heard.

A: So, you’ve failed at being a Popstar… is there another dream that’s next on your list to accomplish?

VS: The big dream for me now is TV. I would love to be a judge or host on some sort of reality competition. That’s where I’d love to go next.

Ameema Saeed (@ameemabackwards) is a storyteller, a Capricorn, an avid bookworm, and a curator of themed playlists, tailored book recommendations, and cool earrings. She enjoys dancing, tattoos, sweatsuits, bad puns, good food and talking about feelings. She also loves to write. She mostly writes about books, unruly bodies, and her lived experiences, and hopes to write an essay collection one day. When she’s not reading books, or buying books (her other favourite hobby), she likes to talk about books (especially diverse books, and books by diverse authors) on her bookstagram: @ReadWithMeemz

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram