The 2021 Scotiabank Photography Award announced their shortlist of finalists last week and Montreal’s Deanna Bowen was one of the four to make the cut.

Now in its 11th year, the Scotiabank Photography Award is Canada’s largest and most prestigious annual peer-nominated and reviewed prize for lens-based art. “Following a year of challenges unlike anything many of us have faced in this lifetime, it is an immense pleasure to announce the 2021 Scotiabank Photography Award shortlist,” says Edward Burtynsky, Chair of the Scotiabank Photography Award jury. “These artists have brought forth important photographic work and it’s exciting to be able to celebrate and honour exceptional Canadian talent.”

It’s a game-changing win, and the the photographer selected will receive:

- A cash prize of $50,000;

- A solo Primary Exhibition during the 2022 Scotiabank CONTACT Photography Festival; and,

- A book of their work published and distributed worldwide by Steidl of Germany.

We were immediately drawn to Deanna’s work, which is unlike anything we’ve seen. Using archival imagery, Deanna share’s missing parts of Canadian history. Right now, her exhibit Black Drones in the Hive is on display at the Kitchener Waterloo Art Gallery (KWAG).

“On the centenary of the first-ever exhibition of the Group of Seven painters, KWAG will premiere Bowen’s Black Drones in the Hive, an interdisciplinary exhibition that reveals the strategic erasures which enable canons to exist without question or complication,” says Curator Crystal Mowry. “By weaving threads of settlement, migration and displacement using local archives, KWAG’s Permanent Collection, publications and propaganda, Bowen excavates the roots of systemic racism in Canada and the erasures that have enabled historical canons to persist without question.”

We connected with Deanna to find out more.

Can you share about what inspired Black Drones in the Hive? Was there a moment in time that compelled you to start looking back in history, or would you describe it as a slow build?

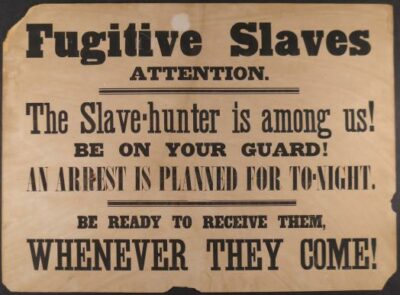

I’ve been making work about family’s history and migration from the US to Canada for 25 years—so, yes I’d definitely say that my practice has been a slow build. Recent exhibitions such as Black Drones in the Hive (currently up at the Kitchener-Waterloo Art Gallery) and The God of Gods: A Canadian Play are in keeping with other projects in that they begin from a family related document and then expands to make site-specific connections to the regional locations & histories of the institutions I am working with.

How did you go about sourcing the archival material, and what was your biggest discovery?

Prior to the pandemic, my research was largely conducted in traditional institutional archives like Library and Archives Canada, etc., family interrogation (hehe) and field research in the US and Canada.

My field trips to Alabama, Georgia, Texas and Kansas have been wonderfully rich, life-changing experiences that have led me to extended family and extraordinary materials. Meeting other “memory keeper” cousins who have shared their incredible research of slave born ancestors is definitely a highlight.

Unearthing a violently foreboding anti-Creek Negro Immigration petition that urged Prime Minister Laurier’s to stop an influx of Black and Afro-Indigenous migrants fleeing racial violence in the US. My family was part of that migration and the petition went on to become an important work that highlights the racist actions of some of Canada’s most important cultural figures.

How did this project make you feel, and what steps did you take to care for yourself in the process? (I imagine it was very emotionally challenging, perhaps traumatic.)

That project was incredibly overwhelming. Traumatic? Absolutely. Infuriating? Check.

As an artwork, that petition became an installation that spanned a 40 ft wall. It’s massive, and the ability to read every signature along with their addresses really showed me how proud these racist people were as well as the federal governments involvement in its production, which really feels quite defeating in the moment. But in time, I was able to turn those folks’ pride into an art work that works to avenge my family for the hardships they’ve endured.

What does being a finalist for this award mean to you?

To be recognized for a practice that has gone against the grain for so long….it’s an astonishing feeling and I am so grateful for this support. It means the world to me.

The winner of the 2021 Scotiabank Photography Award will be announced in Spring 2021. To learn more about Deanna’s work, check out the exhibit at Kitchener Waterloo Art Gallery and listen to her artist talk. For more information about the Scotiabank Photography Award, please visit the website at www.scotiabank.com/photoaward.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram