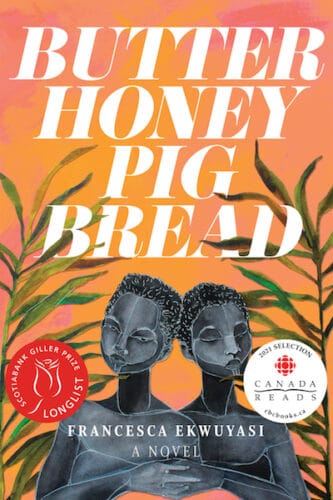

Francesca Ekwuyasi is a writer, filmmaker, and artist from Lagos, Nigeria. Her debut novel, Butter Honey Pig Bread, was a contender in CBC’s Canada Reads debate and is currently a fiction finalist for the 2020 Governor General’s Literary Awards. It’s a magical journey into food, faith, family, and Nigerian folklore—I couldn’t put it down.

Unlike most stories, Butter Honey Pig Bread has three messy and fascinating protagonists: Kambirinachi, a mother who believes she is an Ogbanje, a non-human spirit that brings misfortune to families; Taiye, a queer hedonist who’s on the run from her guilt; and her estranged twinKehinde, who experienced a childhood trauma, and is now on a quest to start a family of her own.

Delicious, vivid, breathtaking, and so utterly alive… I sunk into the story so deeply that the only times I interrupted my reading was to say out loud: “This book is so freaking good!”.

I had the absolute pleasure of chatting with Francesca about her debut experience, the writings that have shaped her, the gaze [we] write for, and the ways that artists, and writers spend a lot of time observing the world, and translating it to other people.

Charming and relatable, she is a breath of fresh air in a literary culture where so often we’re celebrating and honouring the same kinds of stories, and the same kinds of voices over and over again.

—

Ameema: In September 2020, in the midst of a pandemic, you published your debut novel Butter Honey Pig Bread, and only 6 months later, it was a Canada Reads finalist. Now your book is a finalist for multiple other awards. That’s incredible! How do you feel? How would you describe your experience as a first-time author?

Francesca Ekwuyasi: Honestly, I’m mostly overwhelmed with gratitude that people are into it, because the response, or the reception of a book isn’t always reflective of the book’s quality or the artistry of the work, so I’m grateful that people are digging it really [laughs]. [I am] Definitely a little bit overwhelmed – I didn’t expect this much… feedback, but I’m overwhelmed in the best possible way.

I didn’t expect [this reception], but I did ask for it… When I started to write this book, I took a page from Octavia Butler’s book – I don’t know if you’re familiar, but in her journals she would write her desires for her work, and she would write them so specifically.

So, I took a page from that book, and wrote out what I wanted – and it became a bit of a mantra that I’ve started sharing with other artists, and with my friends: What do you want for your work? Let’s name it, let’s say it. So I’m just very grateful.

AS: What are some books or authors that have shaped you, as a writer?

FE: I feel like everything I’ve ever read has shaped me as a writer – even some things where I’m like “yikes”! [both laugh].

I grew up reading Nigerian fiction and folklore, and even though many of these books had characters older than me, or were set in a different time, I knew the neighbourhoods they were talking about, and they felt so close to my lived reality – which gave me the sense that I could write.

I also read a lot of British fiction, like Jacqueline Wilson – books for children, and young adults, about young people being messy. I have also read a lot of Helen Oyeyemi, Haruki Murakami, and authors who have elements of magical realism woven very naturally into their work.

The reason I say everything I’ve ever read informs my style, or my creative choices is because even if a book hasn’t been a pleasure to read, or even if it’s not my favourite, I learn something from it: Like techniques, or that my options are infinite. Actually, Helen Oyeyemi taught me that – she wrote her first book, Icarus Girl¸ when she was 19, and none of her books are the same – so she taught me that I could write whatever I want.

A: I loved each and every character – especially the three main characters: Taiye, Kehinde, and Kambirinachi. They were all so different, but in some ways so similar. As a writer, do you actively work to write parts of yourself into your books? Was there one character that you feel particularly resonates with you? Someone you are most like?

FE: Oh yes! As a writer, I specifically try NOT to do that, but I fail! I remember, a couple of years ago, compiling a bunch of my short stories, and I noticed that there were multiple themes that kept showing up, even though the stories were so different. That made me realize I needed to go to therapy [both laugh], but also, it was so clear that I was processing things in my own life, through fiction, which I don’t think is inherently good or bad… I just really want to write fiction!

So, the character I think that – for better or worse – feels most similar to me is Kehinde, because when I was writing her experiences with just her body and accepting her body, and with fatphobia and racism, and feeling both hyper visible, and completely invisible… That felt so true to my own experiences. Also that rage – I think she’s the least likeable character because she’s angry, and she’s honest about her jealousy… I just dig that character so much.

In my image of the three women, Kambirinachi is sort of simpering, very coquettish, very much a “delicate little spirit person” – even though that’s just the tip of the iceberg, she’s very powerful. Taiye is this wounded hedonist, who keeps saying she didn’t “mean that”, but meanwhile is just hurting people. Whereas, Kehinde was like “yeah, I do mean that. I mean it. I’m angry.” And I love that. I want to be more like that.

A: I feel the same way, all of them felt like people I could have known. But Kehinde, everything about her was real, and it was a lot of those parts of ourselves that we don’t expose to the world, and there was quite a beauty in her honesty. Like, all three of them were kind of messy [both laugh], but they made for such compelling characters. For example, Kambirinachi. One thing I noticed and loved about her was that she was so present in the world at times, but also simultaneously so removed from it… Do you feel like that as an author and an artist as well? Engaged in the world, but also constantly observing it?

FE: Oh my God! Thank you for asking – YES! And I resent it. I’ve been wondering if there’s something wrong with me because of the way it shows up in my personal life, where I feel like “when do I get to be the main character – not the omniscient narrator?”

Which – God, I know how egotistical it sounds – I don’t mean it with any ego, I just want to be the mysterious person being watched…. But I feel like I’m always the watcher! [both laugh]. I think that is perhaps just being an artist – because we’re watching. As someone who writes, I don’t think anything is new. I don’t think we’re creating anything – I think we’re just translating, and to translate, you have to listen; You have to watch. So that is just what it is – blessing or curse – we’re watching, we’re paying attention – that’s the job!

A: This is a book where some really horrible things happen, but it’s also a book that explores the ways we find our comfort, and healing. The ways we move on from hardship. These themes of resilience feel more relatable than ever, as we’re going through a pandemic, and grappling with social upheaval after social upheaval. How does it feel to be writing about trauma and resilience at a time when it feels like we need it more than ever?

FE: This is a conversation I’ve been having with my friends, where we ask – are there more awful things happening right now, or are we just more aware, because of the internet, because of social media, and because we don’t have anything else to do, and we’re all kind of “the observer”.

So, when I was writing this, particularly, the really awful thing that happened to Kehinde, in my own culture, there’s so much silence around it, and I don’t know why. I think it is so painful to go through that kind of thing, and then have everyone ignore or avoid the subject. It felt crucial to write about it.

I also wanted to talk about the general loneliness of leaving home, of being in the diaspora – I say that as someone who has lived in North America since I was a teen, and I always think about the kind of life I could have had. The more settled in a life here I am, the less relationships and connections I have in Nigeria, in Lagos, and that makes me sad… And I say this as someone who is here as a documented immigrant. I have a passport, I can travel, and my country has borders I can go in and out of – but it’s still so lonely – and some people can never go home. And that’s another hard thing I wanted to write about, from a very privileged point of view.

So, having the rest of the world read this now, during a nightmare pandemic, I was worried people would read it, and think it was too much – my intention was not to create “trauma porn”, it was kind of the opposite actually. I always want to write things that are a pleasure to read. I also don’t want to be Pollyanna-ish and pretend that class doesn’t exist, and racism and mental health issues don’t exist, and that spirituality and all of the confusion of what it means to be alive doesn’t exist.

A: I think you did a great job balancing the two. While reading the book, it struck me that all these hard things happened, but there was this undercurrent of… comfort… for lack of a better word… Whether it was a healthy coping mechanism or not, and in Butter Honey Pig Bread you reference a lot of things that bring comfort to your characters. Food, books, cooking, sex, beekeeping, art, faith… What does comfort mean to you? Are writing and creating sources of comfort?

FE: Writing, creating, and reading. Experiencing stories and art. I used to pretend to sleep as a child, and I used to just imagine. I used to fantasize about other worlds, other ways of being, and fantasize myself as completely different, so definitely [writing is] some sort of escapism and comfort. I don’t think I know anyone who doesn’t have a vice, or a thing that they love – like weed, or cooking, or cooking with friends, and it’s just the most human thing – even in the middle of a pandemic.

You know like, Elizabeth Gilbert, mentioned how she volunteered at a refugee centre, and people just wanted to talk about their love lives. That stuck with me because, like… Yeah, you’re still a person. Just because the world is crumbling around you, doesn’t mean you still don’t have a crush! And that’s how I feel in my life, and with these characters. Things don’t always make sense, but we all still want love, and connection.

A: That’s the power of literature, right? Like I’m not going to say that books are the most important thing in the world, but at the same time, there’s this power, and this escape, in reading. There’s a reason people flock to books… We kind of always need these moments and explorations of the joy, beauty, and comfort – and not just the crappy things – that are happening around us.

FE: Yeah, exactly! In Nigeria, there’s a word we use, Wahala, and it means troubles (like really bad trouble), and there’s this phrase “Wahala no dey finish” which means essentially that life is relentless – so might as well have a nice time when we can.

A: This book is steeped in folklore – why was it important to you to explore twin folklore, and Ogbanje folklore in your story?

FE: Well, I’ve always been fascinated with twins… I grew up reading books about twins, and in Yoruba culture twins are revered, and considered deities – Ibeji, and that was just a big area of interest for me.

In terms of Ogbanje, I grew up reading and hearing gossip about it, so I was very interested in the folklore. There are specific facets to the folklore that I didn’t adhere to, because I wanted to write it as fiction, I didn’t want to disturb or attempt to interpret something, so it’s pure fiction – my definition, and explanation of the Ogbanje. But the core idea, which is a spirit that is born, and then dies in childhood – that is true. I wanted to write what I was interested in.

A: I think you did a great job of sharing these pieces of your culture and your traditions, in a way that also made me keep wanting more. I love when a book makes me want to learn more, and I found I kept Googling what things meant, where things came from, what certain ingredients tasted like, and even some of the folklore you mention.

FE: Yes, I’m the same! I love Googling things, but I was a child of the 90s, so when I was younger, it was an encyclopedia. When I wanted to know something, I would look it up and learn from there, and sometimes I would look up the wrong things – like I vividly remember, one time, when I was 10 or 11, I was trying to look up “Sloth” – as in the vice, and instead I looked up “slut” [both laugh].

But yes, I loved having to go read and research! With encyclopedias, and even Google, it keeps leading you to something else – you’ll get the definition, and then something else pops up. And I know that some people they don’t like that – they don’t like to reach outside of themselves, and that is fair… But I was a Nigerian kid reading British and American literature, as a child and a teenager, and have had to do that my whole life – and I feel like that’s okay. Like I didn’t know how to pronounce the name “Siobhan” when I first read it in Helen Oyeyemi’s Icarus Girl, for years! [both laugh] – so it’s fine. It’s research.

A: Yeah, I agree completely! I grew up in Pakistan, and also grew up on British and American literature, and the amount of things that I had to figure out for myself – like who “Santa Claus” was for example. And a lot of people around the world do that extra work, and that extra learning. Personally, I always like it when an author – particularly a racialized or international writes a book that’s steeped in their own culture, and their own names, I actually love it when they’re like “you know what, I’m not going to define it.” I think it’s so powerful, because there’s a lot of presuming a certain gaze when you write a book.

FE: Yes! I was talking to author Jael Richardson about this recently, and we were talking about this, coming from different perspectives – because she grew up here, and I think it’s fine… You’ll figure it out.

A: Yes, and I think there’s a certain amount of “hand holding” that people expect, and if you want to provide that, go for it, but you shouldn’t be pushed to constantly have a glossary because the names are different… Like, we all had to learn how to pronounce Hermione.

FE: Exactly! We’ve learnt it. I have always appreciated when books like Junot Diaz’ The Brief and Wonderful Life of Oscar Wao, or more recently, Zeyn Joukhadar’s The Thirty Names of Night, they use their own languages, and references to their own cultures, and foods, and I’m grateful that authors gave me a chance to learn… And –no shade to authors anywhere—but I’m slightly resentful when things are over-described, and defined, because they’re thinking of a North American gaze, and while that’s there, we all exist in this nightmare, and I think we can be braver.

A: There’s this duality, like in fantasy, where you’ll read a character’s name, that’s just totally made up, and complex, and you’re expected to just take it in stride, and embrace this new made up culture, and learn how to pronounce these words – and we don’t give the same benefit to real, existing people, cultures, and names… Like, whenever I see a writer of colour who doesn’t use a glossary, or pronunciation guide, I feel this surge of “YES!”

FE: Me too! I think the reality is that a lot of that gaze is imagined. Not in terms of power, because the power dynamics are real, and racism is real – but this, I think is the poison of white supremacy, and white oppression and domination – is that it is internalized. So, when I’m alone, writing in my room, I do have the option to imagine how white people will take it, because if we’re thinking economically, they hold a lot of economic power.

I think that [not writing for a specific gaze] is an utter privilege – because I grew up in my country – and I’ve had the opportunity to leave in a documented fashion, because that allows me the opportunity to challenge this gaze, and think about me, and people who look like me. I think it’s privilege because when you are in survival mode, and you have to think about how to sell your book, you want to make sure that people who have money understand it – so I understand why people do it. But it makes me so happy to be able to not do that, and to invite you to learn, because I want to be invited to learn.

A: You’re right, I do think this comes from a lot of privilege, and I recognize that. It’s just personally, I’m tired of reading the same kinds of things all the time, and seeing the same kinds of things reflected on the page, and it’s one of the reasons, I’ve pretty much stopped reading many of the “classics”. Of course, to each their own, but I feel that we’ve put a lot of weight and “legitimacy” into things in the past where if we take a critical look at them now, and viewed them with the same lens that we view a lot of newer books, and books by authors of colour– would these “classics” still stand up in the same way? Honestly, I don’t think so.

FE: I don’t think so either. Sometimes these books just… suck. A lot of these classics are what set the standard, and create the canon, and you can’t separate that from – the patriarchy, and classism and racism.

It makes me think of Alan Yang, one of the writers of Master of None, who in his acceptance speech for the 2016 Critics’ Choice TV Awards, said “Thank you to all the straight white guys who dominated movies and TV so hard, and for so long, that stories about anyone else seem kind of fresh and original.” – and that’s so true!

A: Honestly, I look forward to when people of colour, and trans people, and queer people can just be… mediocre.

FE: I know! Like, I was thinking of this in terms of Black television, especially Nollywood, where it’s part of the style of old Nollywood films to be “bad”. And mediocrity is celebrated, because we’re just happy to have something, and you know what? I don’t hate that. Especially when we’re talking about representation.

A: Do you have any tips for writers who are just starting out?

FE: I think it’s just important to write. I’ve been writing for so long, and I don’t mean to be a weird, encouraging “aunty” – but just do it, because I just did it. I wrote, and I submitted to places. I really want to encourage people because (at least for me) there’s no fantastical secret. You don’t need to have a certain kind of “prestige”, because that’s not what happened for me. You just write. I did it, and you can definitely do it.

—

Ameema Saeed (@ameemabackwards) is a storyteller, a Capricorn, an avid bookworm, and a curator of themed playlists, tailored book recommendations, and cool earrings. She enjoys dancing, tattoos, sweatsuits, bad puns, good food and talking about feelings. She writes about books, unruly bodies, and her lived experiences, and hopes to write an essay collection one day. When she’s not reading books, or buying books (her other favourite hobby), she likes to talk about books (especially diverse books, and books by diverse authors) on her bookstagram: @ReadWithMeemz

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram