When sociologist Dr. Elizabeth Anne Wood discovered that her previously sexless mother had become a Domme, she was happy for her; however, her mother’s revelling in her newfound sexuality was abruptly curtailed when she was diagnosed with an aggressive form of cancer.

Suddenly, Wood found herself navigating the usual challenges associated with caring for a dying parent. But, different from many daughters, she also prioritized her mother’s right to enjoy her sexuality as long as possible, even when that sexuality happened to include BDSM.

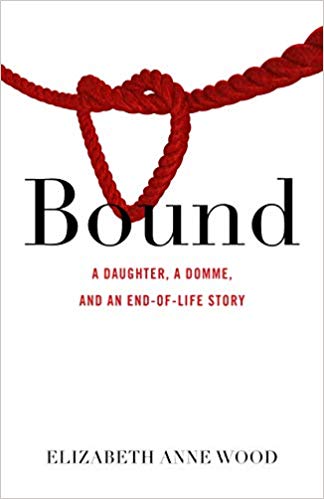

In Bound: A Daughter, a Domme, and an End-of-Life Story, Wood chronicles the last eight months of her mother’s life, a period she comes to see, over the course of months, as a maternity leave in reverse: she is carrying her mother as she dies.

We asked her about the book this week.

SDTC: How did you uncover the fact that your mother had become a Domme after years of sexual inactivity?

It’s a funny story, actually. My mother and I always talked easily about sexuality, and I was studying sex work while writing my dissertation. One day my mom went to an interview for a freelance copy editing job, and when she returned she called me up and said, “Did you know you could get paid to hurt men and you don’t even have to have sex with them?” It turns out she’d been given some adult magazine ads to copy, and she’d been particularly interested in the ones for dominatrix services. I knew she’d been unhappy in her past relationships with men; of her two longest, the first had been deeply unsatisfying and the most recent was abusive, and that one had been almost twenty years earlier. I was excited that she might be finding a way of relating to men that would offer her some pleasure and power. She clearly wasn’t ready to dive in just yet, but a few years later she was, and she spent several years enjoying herself immensely.

My initial reaction to that first phone call was a blend of excitement and apprehension. I do think, though, that what BDSM gave her was a sense of control that she’d never felt with men before, and that allowed her the freedom she needed to experience eroticism and pleasure.

Shortly after, your mother learned she had cancer. How did she process that information?

We were both terrified and devastated. Her initial diagnosis was kidney cancer, and the prognosis was good if the cancerous kidney could be successfully removed before any of the cancer had spread. While facing that, though, my mother revealed that she did not think she could live if she had to be on dialysis for the rest of her life, which was a risk. I assured her that if it came to that, she could live out the end of her life on her own terms. As it happens, just a few months after her surgery, her remaining kidney failed and she was faced with the situation she’d just month’s before told me she didn’t think she could live with.

I believe that her BDSM experience, and the community support she found there, gave her the will to live and a toolkit for managing life on dialysis that ended up making the last three years of her life among the happiest she’d ever had.

How did you come to grips with her diagnosis?

I did what I always did when her life got chaotic or manageable: I took notes, made order, and did as much caregiving as I could. That meant that sometimes I was not as daughterly as she might have liked. This is something I write about in my book: the special kinds of role conflict faced by family caregivers, especially by daughters.

What did going through this experience teach you?

The biggest lessons I learned were related to caregiving and mortality. I learned that it is very hard to be an affectionate, warm, supportive daughter while also trying to be a medical advocate in the face of a complex and terminal illness. I learned that it was much easier for me, in fact, to take on the medical advocate/caregiver role because it allowed me an emotional distance from my mother’s suffering that would have been harder for me to face if I were “simply being the daughter.”

I also learned a lot about what medical intervention looks like when a person is nearing the end of life. There is this ongoing tension between treating the disease on the one hand and easing the symptoms on the other, and between prolonging life on the one hand, and protecting the quality of that life on the other.

In part as a result of watching my mother’s slow slide toward death, I’ve learned that I do not want treatment to try to slow a disease that is going to kill me if that treatment is also likely to make me sick. I accept that dying is part of living, and that I want my death to be as peaceful as it can be. If I can combine treatment with excellent palliative care, and have both peace and longevity, then that would be wonderful. If that means a shorter life, but one with less pain and suffering, then—at least right now—I’m okay with that.

What do you hope readers take away from this book?

There are several things I hope readers take away from this book but forgiveness and empathy are at the top of the list. Many of us are or will be caregivers and we won’t do it perfectly. We need to approach the people for whom we’re caring with empathy, and we need to be able to forgive ourselves when we make mistakes. We need to be brave and open to having hard conversations, and we need to be supportive and encouraging when others are struggling with those same conversations. Honestly facing these challenges is hard, because our relationships are often so fraught with baggage from the past. I hope that my story helps others move through their own.

I hope that people come away from this understanding that sexuality is an important part of our whole selves, and that it doesn’t necessarily disappear or wane as we age or when we are sick. Certainly some people experience that and others don’t, but retaining a desire for romance, intimacy, sexual pleasure isn’t unusual. As a society we tend to infantilize the aging and the ill, and the healthcare system does this even more dramatically. We need to stop that. We need to treat people with illnesses as whole people, and not as clusters of symptoms or as embodied diseases.

I want people to come away with the knowledge that if they’re struggling with caregiving and medical advocacy because of role conflict, or because of the byzantine nature of health care bureaucracies, that it isn’t their fault. This is the nature of health care in the United States, and it’s important to try to create a support network around us as caregivers to help us help the people we’re caring for.

How can we better support our parents in their decline?

I want the book to open space for important conversations about caregiving, end-of-life care, sexuality, and dying. About 40 million people—that’s more than 1/10 of the population—are caregivers in any given year. Quality of life, especially at the end of life, rests on several things, but one foundation is good communication. People, as they are aging, need to talk to the people who love them about what kind of care they want as the get old, or if they get sick. And those are not one-time conversations. People’s ideas about care needs, or end-of-life wishes, develop and change over time.

Patients and health care providers need to be able to talk about a person’s needs for intimacy and pleasure, and need to be able to discuss how the care they receive will affect it. They also need to be able to talk about how to adapt to those effects, or how to accommodate the person’s sexual relationships or desires as best they can. These conversations are hard, and my hope is that books like mine will help people have some of those difficult conversations. It’s often easier to open a conversation if you have something to point to or share that isn’t immediately personal, and so I hope this book will serve as a conversation starter for many people struggling to approach these issues on their own.

Follow Us On Instagram

Follow Us On Instagram